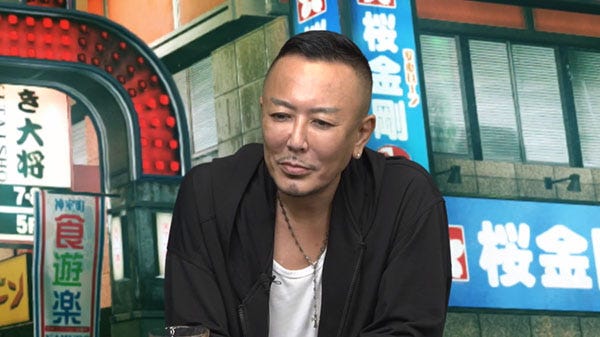

An extremely bad interview with Yakuza creator Toshihiro Nagoshi

I’ve had a few bad interviews, but this particular encounter at E3 2019 made me want to crawl inside my own shoe and die.

Let’s start with some context. First off, it’s hard to fly 11 hours across the world, go back in time eight hours, and function on four hours of sleep per night. It’s tough to talk to people all day and be around all the loud noises with no escape, even in your hotel room that you share with your (absolutely great, please don’t fire me) boss.

Despite all this, you get by on the buzz of the thing. It’s E3, man. E3! The Electronics Entertainment Expo - gaming’s Mecca and the chance to talk to loads of interesting, intelligent people about the cool s**t they’re making. It’s extremely good, in the same way suplexing your brain into a skip is good.

Yakuza creator Toshiro Nagoshi was feeling the same when I went to interview him on the second day of the show inside Sega’s booth. I arrived ten minutes early and my interview was ten minutes late - that’s when I started to wonder what was going on. It turns out Nagoshi was asleep in one of the interview rooms and I was kindly offered an interview with someone else. The problem was, the questions I had prepared were for him specifically. As the brilliant PR person and I try to figure out what to do, a door opens and we can clearly see Nagoshi-san rising from unconsciousness through the crack.

It was at this point when I realised I’d fucked up.

I was led into a small interview room where Nagoshi was sitting, along with a PR person and a translator. I could already see that he hated me for existing. He had literally just woken up and here’s this guy bothering him as loud music and annoying noises blare from beyond the thin walls and through the open ceiling.

“I'm sorry to interview you when you're so tired,” I joke, laughing by myself as Nagoshi’s eyes roll into his head. “I'm only going to do a quick one anyway, but I wanted to start by talking about your research process. I wondered if he'd consulted with any real Yakuza on his games?” I direct my question to the translator.

“He's - what sorry?” replies the translator, unable to make out my question above the horrible sounds seeping into the room combined with my East Midlands accent.

“Consulted with real Yakuza,” I repeat.

“Consulted, oh,” the translator replies before relaying my question to Nagoshi.

A decade passes.

“No, there was no actual consulting work,” comes the reply. “So there was actually already a lot of reference materials sourced from, like there's a lot of Yakuza-themed movies and books and comics and things like that to draw from.”

At this point, I’m looking for a hook - a good personal anecdote to kick off a story about Nagoshi and the kinds of games he makes. I try another approach.

“He said previously in another interview that he drew from his time going around drinking, hearing sad and funny stories from the people he met. I was wondering if he could tell me any of those stories,” I ask.

“He said it in another interview?” the translator replies.

“Yes, he said that he learned some sad and surprising stories,” I clarify.

“From Yakuza?” comes the response.

“No, from going around drinking, just from people in bars and stuff,” I clarify more.

“Oh, okay…”

I cut in to make sure the translator understands the angle, “And he incorporated that into the games, he said previously. I was wondering if I could get some examples.”

“So, there's not one in particular, but he does remember each [inaudible because of the hellish sounds beyond the booth] that he heard from [inaudible] that he talked to, and it's usually the people that work at these bars that he's acknowledging that they've arrived at this point in their lives because they faced some hardships in their lives growing up, or they went a little bit overboard in their youth and they're trying to kind of correct their path, sort of, and redeem themselves, and that sort of thing, so that all did really inspire the storyline for this,” the translator tells me.

“And did you draw from any of your own experiences at all?” I follow up in an attempt to get something more specific.

“So, you know, nothing was put into the game as in, like, a life, episode of life, but definitely like some perspective on things, or like if he had seen something in the newspapers, some kind of incident, he would kind of imagine on his own, like what got up to this thing, or what kind of thing happened, and put those kinds of things into the game as well,” the translator replies.

At this point I realise I’m not getting anything raw, personal, or specific from this line of questions so I switch things up a bit and dig into his design ethos instead.

“A lot of his characters are morally grey, but they often don't kill. I was wondering where his preference comes from there?” I ask.

“That's like in battle and stuff, right, they don't kill?” asks the translator.

“Yes, they knock them out,” I clarify. “They're usually like bad-but-good guys, you know.”

A century passes.

“So I mean there are characters that die just throughout the storyline obviously, but I feel like it's kind of a Japanese way of approaching it, and also just a personal preference of my own, I don't really like to go that far in battle,” Nogoshi says, via the translator. “It's just kind of my personal style that's more reflective [another hellish noise blasts over a nearby speaker, drowning out the end of his answer].”

Nagoshi hasn’t looked at me this entire time and I’m pretty sure he’d like to hit me with a giant cone. Still, the answer is a bit more interesting and he seems more open to talking about his approach to design, so I continue down that route.

“A lot of your games share the same locations, the same cities in Japan. How do you make them feel fresh through subsequent games?” I ask.

“So the players of today are totally different to players of ten years ago, and so we try to evolve and incorporate more new things into the gameplay and into the setting so that it changes with the times, and evolves so that the players of each new generation and new time will be able to find something that they enjoy in it,” he replies via the translator. “And we do pay close attention to [another noise from the pits of hell seeps in] and the details of games and try to make adjustments so that [bwarp].”

I nod my head and pretend I heard what he said.

“Judgment shares the same world of Yakuza, right?” I ask. “But it's a different kind of story. I was wondering what drew him to this particular story?”

“Sorry, what?” the translator replies over the bwarps.

“What drew him to this particular kind of story this time?” I repeat.

An eon passes.

“So we were confident that if we took all of the know-how and the skills and the knowledge that we took away from creating the Yakuza series throughout the years we would be able to create something new that would be really good at bringing that experience, so that was kind of the new challenge that we wanted to take on with Judgment,” Nagoshi explains via the translator, his eyes getting more furious with each question.

As he’s answering that last one I take a look at my list of questions. One of them is about Pierre Taki, a Japanese actor who lent his likeness to one of the characters in Judgment. He was removed from the game following cocaine use allegations. I wondered how Nagoshi felt about that, but I also got the vibe that he would dropkick me in the eye or walk out of the room if I asked it. Best skip that question about Shenmue 3 while I’m at it.

“Originally the Yakuza games were made for the Japanese market, but now they're popular in the West. What do you think is behind that? Do you think gamers are just sick of being in America as a setting for video games?” I ask instead.

“So that might definitely be one reason for that, that gamers in the West are bored of certain environments, but also it's not just Japanese games being accepted in the West, it's also the same thing is happening in Japan, where they're really more open to Western experiences,” the translator relays Nagoshi’s answer. “So it's kind of a trend that the worldwide thing right now, where everybody's becoming more open to new experiences.”

At this point, the translator gets a strange, horrified look on their face and I get the sinking feeling that I wasn’t given Nagoshi’s full response. I press on regardless, fighting my own urge to go to bed.

“How do you feel at the moment about the health of the Japanese game development scene compared to the West? Does he feel like one does anything better than the other side, or vice versa?” I ask, the end of my question drowned out by a distant bwarp.

“Sorry, the last part?” says the translator.

“Does the West do better at certain things or does Japan do better at certain things, I was wondering?”

“So Western studios are, I really feel like there's a much bigger budget attached to a game usually and so the scope of the game world is much bigger, and it's on a larger scale,” comes his reply. “But in comparison to that, Japanese developers are more, really good at looking at the details, and really putting excellent craftsmanship into each and every one of their titles, so they both have their pros.”

I say my thanks and leave, knowing that I likely don’t have anything useable in the interview. At least we have this article though, eh?

I would like to add that it was a honour to chat to Nagoshi-san, and the PR and translators did a wonderful job. This article is meant to highlight the weirdness of E3 when you’re there in person and everyone is walking around like ghosts who died again after they turned into ghosts, their howls of pain drowned out in bwarps. I can still hear them now. The bwarps, I mean.