Wonder Boy: Omar Cornut Is Building His Own Miracle World

A lengthy conversation with one of the gentlemen behind LizardCube, the developer of Wonder Boy: The Dragon's Trap.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

It's been an adventure for Omar Cornut.

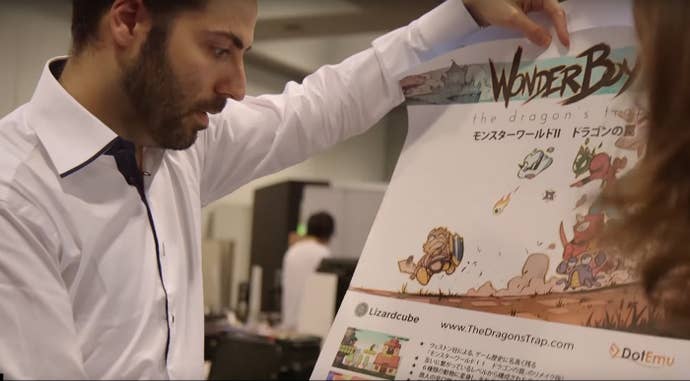

Omar Cornut is a founding member of LizardCube, the studio behind the remaster of the Sega Master System classic Wonder Boy: The Dragon's Trap. Together with animator and artist Ben Fiquet and a host independent developers, Cornut brought back a lost classic on modern platforms. Wonder Boy: The Dragon's Trap looks backwards as much as it does forward, allowing players to switch between the original game and the remaster at the press of a button.

He's a fast-talking tinkerer. You get the feeling that he's always thinking about something, always attempting to push his personal boundaries forward. He's worked within the industry on a number of platforms, but Sega and the Master System were instrumental to some of his earliest work. Cornut's ongoing efforts and his career have taken him worldwide, from his home in France, to the United States, Japan, and England.

Press Start: The Emulation Era

For Cornut, the Sega Master System was his first console, but it wasn't how he discovered games. That happened during his family's move from France to Egypt in 1987. Everyone had an Atari, but Cornut's best friend had one of the early Sega Computer Video Game systems. A year of playing on the console brought something in him to life. And when his family moved back to France a year later, he picked up the new Sega Master System.

Cornut returned to the Master System again in 1996-1997, when desktop PC emulators started to see a rise in prominence. Personal computers had gotten to a point that they could potentially replicate what was being done in earlier video game consoles, with hobbyists reverse engineering those consoles in code. Emulating guru Marat Fayzullin, who also coded iNES, fMSX, Speecy, and Virtual GameBoy, had already released MasterGear, which emulated the Master System, GameGear, SG-1000, SC-3000, and SF-7000. Cornut started dumping Sega games for MasterGear, which eventually led to him creating his own emulator, MEKA.

"I had been learning programming for a few years. I was a student and I did that on my spare time basically. It led me to both write a Master System emulator and start a community of people obsessed with all Sega games," says Cornut. "Part of my hobby was making digital backups of these games."

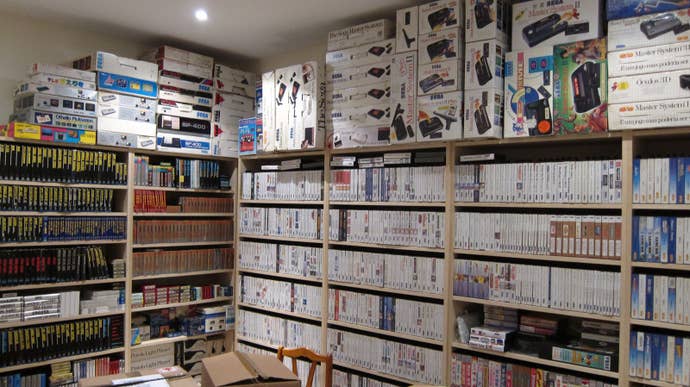

That community, SMS Power!, is still around today, dedicated to preserving everything related to the early era of Sega hardware, including the Master System, Game Gear, SG-1000, and Sega Computer 3000. The site collects and archives retail releases, unreleased titles, software and hardware prototypes, and more. Cornut himself has a huge Sega collection, due to a quirk of MEKA's product registration process.

"My emulator was in the MS-DOS days. In the text file, I said 'This is cartridgeware', so people would send me a cartridge to register the product," says Cornut. "Before I knew it, I was receiving games every day at home. My collection built up from users of that emulator. Once I started doing this archive, scanning, and dumping work, it's never left me."

Cornut retains a huge stock of vintage Sega products that currently sits in storage because his Paris apartment can't fit the entire collection. He still acquires odd games and prototypes. Two years ago, he picked up a prototype Sega Master System graphic tablet that was never released. Cornut acknowledges that it's not work that Sega would officially condone, but he believes that part of the company's history is "unpopular enough that it doesn't make money for them," so they turn a blind eye. He's spoken to a number of Sega people in Japan and they're just happy that the archival is happening.

Since he was receiving games from all around the world, Cornut dumped many of the available ROM images for MEKA and other Master System emulators. Dumping and archiving the ROMs led to Cornut doing more coding work, because he needed some way to keep track of the different versions and builds of each title.

"That led us to reverse engineer a game's code, to be able to tell if one version was earlier than another. That's how I learned how to study these old games. This is how Wonder Boy started eighteen years later," he says.

"I've always been into polishing things, more than making something that's totally new. That's what MEKA was about at the time."

MEKA followed MasterGear and other emulators, but Cornut thinks it took off due to the packaging. Most other emulator writers weren't concerned with their work as a product. They wanted it to play games; offering a good user experience was always secondary.

"Frankly, I had no idea what I was doing. I still have no idea what I'm doing, but I had this knack for packaging things and making a full product of it, whereas at the time, other emulators were command line based. MEKA was one of the earliest that was a full, nice-looking product," Cornut tells me. "I've always been into polishing things, more than making something that's totally new. I like to make something and spend time polishing it. That's what MEKA was about at the time."

His work on MEKA was the beginning of a theme with Cornut: he didn't start the project with the aim of learning anything new. It was a passion project. The endgame was the focus, everything else along the way is just a wonderful benefit. Omar Cornut just wanted to do something, so he did it and learned something new.

"That was my approach. I wanted to make it happen more than I wanted to learn," he says. "I didn't see it as a learning process. Effectively, that's how I learn things, but it was just me trying to make the games work. As I found new games from other countries, I would try to make them work. I still do it today. When I get that odd Korean game that no emulator supports, I have to make sure that at least one emulator works with it and others will follow eventually. [MEKA] is a bit broken, but it sorta plays all games."

The School Years

A few years into his work with MEKA, Cornut decided to go to a school that would cultivate his love of game development. In 1999, Epitech (short for European Institute of Information Technology) began its inaugural year. The school promised to provide a cutting edge education in computer science and information technology. Omar Cornut was one of the first students at the school. Unfortunately, Epitech's reality did not match up to the promise in those first few years.

Cornut remembers Epitech as "very disorganized." It was a micro-school with 60 students and no one knew what to do. The teachers were in the dark as much as the students. Despite the ramshackle nature of Epitech, Cornut thrived in the environment. There was no game development program at the school, but like Cornut, there were other students who were interested in making games, so they crafted their own program.

"It was a very nice time for me. Obviously it was easier for me than most students, because I was already programming," he says. "We actually managed to ship four Dreamcast games. They were the first homebrew games made in 3D. They were totally rubbish, but it was a time where we didn't have much middleware."

While he was at school in Epitech, Cornut took his first real steps towards an official job in the gaming industry. He was working for a computer-focused magazine in Paris and game developer In Utero was looking for an intern. They placed an ad in the magazine, meaning Cornut had access to the job posting before anyone else. In addition, he work on MEKA gave him a leg up over any competition.

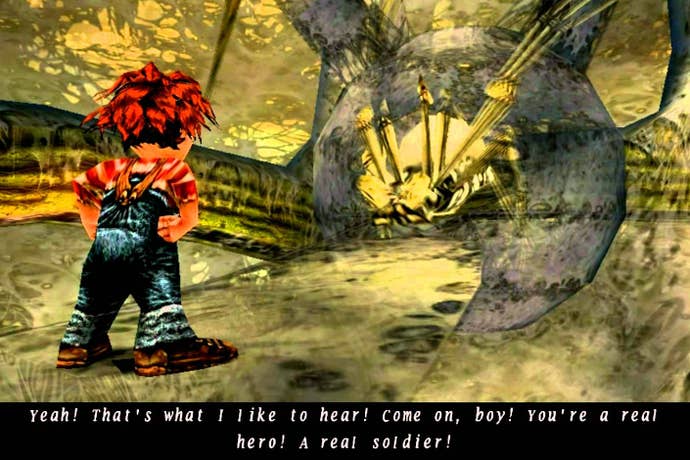

So Cornut was now working at In Utero as an intern, on a game that would eventually ship in 2001-2002. That game was Evil Twin: Cyprien's Chronicles, published by Ubisoft on PlayStation 2 and PC, with a Dreamcast version published by BigBen Interactive. He divided his time between coding tools and designing Dreamcast Visual Memory Unit mini-games for Evil Twin, while working with fellow students on Dreamcast homebrew titles.

"I was a young kid [at In Utero], just an intern among 30 people. Being dropped in the middle of that chaotic—it was quite a tough development process," Cornut says of his time at In Utero. "The game was very ambitious, but eventually just ended up dragging. Being late, being buggy. By the time they shipped it in 2002, the Dreamcast was already dead and buried. Even if my contribution was small, I learned a lot of things there. I learned C++ there."

Epitech's degree program was meant to cover five years, so Cornut attended the school from 1999 until 2004. During this time, he solidified his goal as a young game developer: he wanted to work in Japan at a Japanese studio. In 2003, he buckled down and took a shot at his dream, buying a place ticket and flying to Japan. The journey was neither a complete failure, nor a complete success. He went straight to the offices of United Game Artists, the developers of Rez and Space Channel 5. Armed with a desire to make games and a bottle of wine, Cornut asked to be hired at the studio.

"I spent an hour with Mizuguchi-san and I couldn't speak Japanese," Cornut remembers. "He told me, 'Learn Japanese, come back, and we'll hire you.'"

Joining The Game Industry

For his first official job as a game developer after Epitech, Cornut went international, heading West, not East. He joined a small studio in the United States called Taniko. The studio was working on a game for unannounced Nintendo hardware, which would eventually be revealed as the Nintendo DS. Working on new hardware was what convinced Cornut to travel to the US. The game in question was Retro Atari Classics, a collection of classic Atari games with new visual modes crafted by Californian street artists.

Cornut remembers the process of working on early Nintendo hardware to be difficult because the company kept information close to the vest.

Editor's note: This section has been edited post-publication at the request of the interviewee.

Cornut's time in the United States was short-lived though. While at Taniko, he began working on his own game prototype for the Nintendo DS, since that was the platform he had access to. He went back home to France, where he connected with his friend Olivier Lejade, who had founded a company called Mekensleep. Lejade gave Cornut space and resources to work on his prototype, with both men hammering out the design for a game which eventually became known as Soul Bubbles. At Mekensleep, veteran developer Frederick Raynal (Little Big Adventure, Alone in the Dark) helped with the game's design, while the lead artist was another young man named Ben Fiquet, who would later handle the art on Wonder Boy: The Dragon's Trap. "It was the first product I did A-to-Z. I was very lucky. It's where I learned the most," says Cornut.

"I spent months and months trying to fight with physics and math problems. I had no idea how I was going to solve it."

Working in Japan at Sega or a Sega-adjacent studio was still Cornut's goal, meaning he had to make learning Japanese a priority. The problem was Soul Bubbles' development started to take up more and more of his time. There just wasn't time for Japanese. "In 2004, I did a Japanese course for a year," says Cornut. "The first year of Soul Bubbles, it was part time, juggling the Japanese class. The second year, I basically stopped going to class. My Japanese was never great, but I had a base to survive in Japan at least."

Soul Bubbles finally launched in 2008, after three and a half years of development. It was Cornut's longest development project to date and the first one where he was a lead. It taught him a great deal about game development with real stakes; Mekensleep resources were going to Cornut's prototype and Soul Bubbles' unique physics-based design meant he wasn't always sure things would work out.

"I spent months and months trying to fight with physics and math problems. I had no idea how I was going to solve it, but we found ways," Cornut admits. "By the time we pitched the game to Eidos, we had a pretty decent prototype. Lots of the games I've worked on, there was a moment of total despair in the middle of the project. PixelJunk Shooter and Tearaway, there were moments where nothing worked."

Soul Bubbles was a critical hit. In 2008, it won several IGN awards, including Best Puzzle Games, Best New IP, and Most Innovative Design. Gamasutra called it one of 2008's most overlooked games. It was also nominated for the "Best Debut" award at the Game Developers Choice Awards and in the Handheld category at the BAFTA Video Game Awards. The experiment had paid off for Cornut and Mekensleep.

After finishing Soul Bubbles, Cornut shifted again, going to work for Darkworks, a French developer known for Alone in the Dark: The New Nightmare and Cold Fear. After being a lead at a smaller studio, he wanted the chance to work at a big one under some veteran developers. Darkworks had worked with Infogrames Entertainment and Ubisoft, so it felt like the right fit. Darkworks was working on a game for Ubisoft when he joined: a survival title called I Am Alive.

"I was fantasizing about learning from senpais and teachers," he says. "They had been working on it for our years already. I arrived there and it took me a few days to learn that everything was terrible. They were in the middle of the trenches. It was not my baby, so I basically left after a month and a half. I was lucky to be unattached to it."

Darkworks began development of I Am Alive in 2003 and continued to toil away on the project until 2009. Ubisoft eventually pulled the game from the studio and moved its development to Ubisoft Shanghai. The Ubisoft studio scrapped most of the work Darkworks had done and rebooted it with the same concept. Cornut doesn't regret leaving Darkworks before he got invested, but he still wants to work for a huge studio like Naughty Dog or Blizzard Entertainment in the future. "Some part of me would still like to understand how a big company that is functional works," he laughs.

Heading To Japan

Cornut was free from Darkworks, but he didn't have a job at another studio. He still wanted to go to Japan and work for Sega. United Game Artists was gone though, having been absorbed by Sonic Team in 2003. Ex-UGA designer Tetsuya Mizuguchi had left to form his own studios, Q Entertainment, so the chance to work at Sega under him was gone.

Cornut would end up working for another studio that began with "Q". He applied to Q-Games in Kyoto, Japan, a new studio that was founded in 2001 by an English developer named Dylan Cuthbert. While working at Sega or another Japanese company might've been a problem with Cornut's limited Japanese, Q-Games was a better fit. "With Q-Games, 40 percent of the employees were foreigners," Cornut tells me. "It was a foreigner-friendly company and it still is. It was our job to learn Japanese, so I did some Japanese classes there. My Japanese wasn't perfect."

Q-Games had become a second-party partner for Sony Computer Entertainment, working on the PixelJunk series of games for PlayStation 3 and PlayStation Vita. Cornut was assigned to work on PixelJunk Shooter. What he wasn't prepared for was the quick and iterative nature of development at Q-Games. PixelJunk Shooter only took around 15 months of development time. He loved it. "It was an amazing experience. I was able to learn from very different programmers and artists how they do things. That fed my desire to learn from others," Cornut says.

"When we made Soul Bubbles, the game evolved slowly. Whereas [at Q-Games], they were structured to change everything any time."

"When we made Soul Bubbles, the game evolved slowly. Whereas [at Q-Games], they were structured to change everything any time. I remember being shocked and surprised the first time we sent a build to Sony, they basically changed the rhythm, setting, and shooting a few hours before that. We had a semi-working game and they changed everything. It was very aggressive iteration. That's something that I've been doing ever since."

Cornut finds that making big changes is his preferred method of development. He points to a quote attributed to Civilization designer Sid Meier. "If you want to tweak something, like a value or setting, double it or halve it. Don't tweak it subtly. Make the extreme change and that's probably going to tell you that it's much better or worse," Cornut says.

Following his work on PixelJunk Shooter, Cornut moved to a project named PixelJunk Lifelike. It was a music game planned with Q-Games music director Baiyon. Baiyon and Cornut worked on the prototype for Lifelike, but the game wasn't coming together. "That was a catastrophe. I think they trusted us too much," Cornut explains. "Baiyon was director, but he wasn't really involved because he was doing fifty other things at the same time. I was the only other person on it." I hear Cornut's frustration with the development of PixelJunk Lifelike, even though the game released years ago.

Despite that poor process, Cornut learned from it, specifically in the development of his tools. The project was going nowhere and Cornut kept himself active by making tools that he felt Baiyon would eventually use. The problem is Baiyon wasn't just busy; even when he was around for the project his desires weren't quite clear. "Baiyon is an artist and very vague. That was a total failure for a year," says Cornut. The relentless march of useless tools development gave Cornut his own concrete ideas about making development tools.

Eventually, Q-Games management stepped in and rebooted the game as PixelJunk 4am. It was a seven-person team with a brand-new designer. Sony stepped in to offer marketing support if Q-Games would add PlayStation Move support to the title. Development became more enjoyable with more structure.

"We started turning the game into a Move title," says Cornut. "We made a silly video of us dancing in the forest, because [Q-Games founder Dylan Cuthbert] started getting into making movies. He bought all these cameras. It was fun. I remember Baiyon hated it because he was cultivating a certain image of being serious."

During his two and a half years at Q-Games, Cornut worked on three games: PixelJunk Shooter, PixelJunk Lifelike/4am, and PixelJunk Shooter 2. In the end, he found that working in Japan wasn't really for him. Cornut had achieved one of his goals, only to find out it wasn't what he wanted. "Working in Japan, the games were great," he tells me. "Working at Q-Games wasn't for me. It was not easy. I'm not an easy person to work with. I'm never satisfied. I'm a butterfly in a way. So I wanted to go. I didn't feel at home and wanted to go back to Europe."

Tearing Away In England

Having been in the industry for some years at that point, Cornut had made friends. One of those friends, David Smith, became a founder at Media Molecule. It was 2011 and Cornut was looking for somewhere else to work, so he applied at Media Molecule. They didn't answer him, but two months later, he connected with Smith, who told him they never received the email. Cornut went to work for Media Molecule. Problem solved.

Media Molecule was already beginning work on Dreams, which some may remember from Sony's press conference at the 2015 Electronic Entertainment Expo. Following the development of LittleBigPlanet 2, the studio was too big, so while some of team went to work on Dreams, a few were split off to create a game for Sony's fledgling PlayStation Vita. "They basically put Rex Crowle in a room and had just received the Vita prototype dev kit. They let Rex do what he wanted," says Cornut.

Rex Crowle was working out the concept for the game that would eventually become Tearaway. Tearaway was conceived as a quick, year-long development effort for the Vita. It took two and a half years before it was done, because the original concept was a completely different game. When Cornut joined the project, it was four or five people in a room.

"At the time, it was an isometric, 2D procedurally-generated, geolocalized game," says Cornut. "It had nothing to do with what Tearaway became. It was basically a dungeon crawler with your finger. The SKU was supposed to have 3D. If you started the game in France, you'd be in virtual France. The game would ask you to travel the world."

The problem, the game was technically sound, but it wasn't fun. When it came time to demo the game to Sony, one developer made the levels by hand instead of relying on the procedural-generation system. All of a sudden, Tearaway was enjoyable, prompting a change in its development focus. Tearaway shifted from its technology-centric original concept to become something far more traditional.

Despite that, the game's unique look and use of the Vita's dual touchscreens made Tearaway one of the marquee games on the system. It was well-reviewed. Tearaway went on to gain eight nominations and three wins at the 2014 BAFTA Video Games Awards, five nominations at the Game Developers Choice Awards 2013, five nominations at the DICE 17th Annual Awards, and three nominations at the Develop Award 2014.

Following the completion of Tearaway, Cornut also put in some time on Media Molecule's long-running Dreams project. "I worked on Dreams for a year or year and a half. Dreams was rebooted probably four times, because it's very ambitious," says Cornut. "It's going to be incredible I think. It's so ambitious that they're never going to finish it. Maybe they will, but I don't know how they're going to do it. They're good enough that they'll figure it out."

Eventually, the development butterfly decided he needed another change. From London, he freelanced part-time with Wild Sheep Studio, a company founded by Rayman creator Michel Ancel and former Ubisoft employees Celine Tellier and Christophe de Labrouhe. His work was done with Pastagames Studio, a Parisian developer who's handling the engine for Wild Sheep's upcoming survival game WiLD.

Entering The Dragon's Trap

Cornut was done with Media Molecule and heading back to his native home of France. It was time to try something different again. He decided that he wanted to start his own studio this time around, but the major question remained: What type of game should his company make? In the end, he made a pragmatic choice. Instead of making a brand-new game, why not start with something old?

"Wonder Boy was part of me knowingly saying, 'I'm going to make this because it's my comfort zone, I know the Master System technology.' It was a mixture of aligning my interests: Sega Master System and making games. It was a game I was fantasizing about for fifteen years. I always wanted to make something with the series," says Cornut.

"It was also sort of a cop-out in a sense that I wanted to start my company, but I knew that designing a new game is so terrifyingly hard. I was happy to make something that seemed easy. It's always ten times harder than you realize, but making the game was still comparatively easy. I've been wanting to do it for so long that it was easier to scratch that off my list."

With his new company, Cornut wanted a chance to look at the other side of making games: promotion and marketing. Being a programmer for his entire career, he was a behind-the-scenes developer, not talking to players and getting the game in front of people. For Wonder Boy: The Dragon's Trap, he'd be running the Twitter and Facebook accounts. He'd be updating the dev blog. His new company, LizardCube, wasn't a one man show, but more of the overall work fell on his shoulders compared to past projects.

Despite Cornut's love of another classic Sega property—his official website is "Omar Cornut in Miracle World" at miracleworld.net—he chose Wonder Boy over Alex Kidd for his project. Wonder Boy: The Dragon's Trap, when you stripped away the nostalgia, was still a game that withstood the test of time. It still played well.

"Dragon's Trap aged quite gracefully. It's a retro game, so it's rough in ways, but it's still quite pleasant to play. It had this quality where it was great enough for an old game to hope that it would sell," says Cornut. "There's a lot of weird Master System games that I love, but nobody would care about them. If we took Alex Kidd, we would have to make a new game and I was trying to avoid making a totally new game."

Sales were important. Cornut was independent now, meaning it was his own resources being consumed. It wasn't enough to work on a passion project; he wanted a game that would be profitable. His career up until this point had a number of games that he was proud of, but he wasn't sure if they really made back their development budget. "I think that none of the games that we spoke about before were profitable," Cornut says. "With long tails and sales on Steam, they were, but depressingly enough I think most of them weren't a success. In spite of them all being good."

Wonder Boy: The Dragon's Trap was a game that Omar was already messing around with on his spare time. He had been looking through the game's code to find any hidden secrets, pulling all of the levels straight from the original ROM. He decided to try reverse-engineering the entire game and that hobby work eventually ballooned into something worthwhile. Cornut knew who would be interested in remastering Wonder Boy too: former colleague and animator Ben Fiquet.

The pair had an idea, but the problem was they didn't have the rights. Worse, the rights to Wonder Boy are spread out. Sega owns the trademark, but another company called Westone owns the property. The entire franchise was a bit of mire, stretching across Wonder Boy, Monster World, and Adventure Island properties. So they went to the game's creator and original designer, Ryuichi Nishizawa, to pitch the remake. "He gave an informal 'go.' We didn't have a contract, but he was like 'Yeah, you can do it.'" Cornut says.

They were still missing a part of the rights though. The part currently held by Sega. Cornut didn't want to approach the company for the rights. As the game grew bigger, the team looked for funding and a publisher. That journey ended with DotEmu, a publisher that focused on retro projects. It was DotEmu that stepped up and pushed LizardCube to talk to Sega about acquiring the license. "I didn't want to do it myself. I'm glad that DotEmu convinced us to get this license, because it's helping us with the reach," says Cornut.

Rebuilding A Classic From Scratch

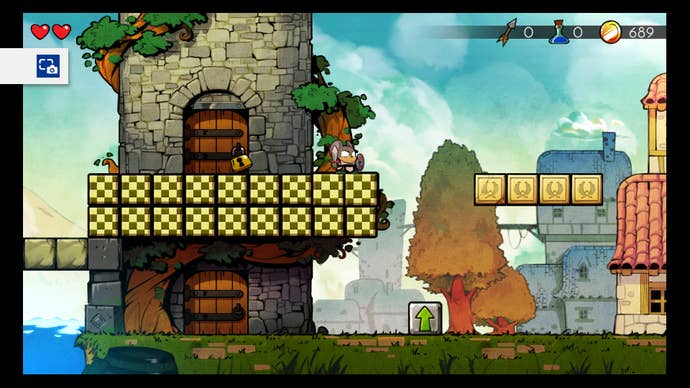

The idea was there. The license was on hand. Now the team at LizardCube had to actually build Wonder Boy: The Dragon's Trap from the ground up. Cornut calls the final product a "Frankenstein technology" of coding. While the initial plan was to translate and rewrite the game's code, Cornut found that method "very painful and error-prone." He decided instead to start with emulation of the game and then build any additional technology on top of that. So the remaster isn't a complete rewrite of the game for new platforms; in part, Wonder Boy: The Dragon's Trap is running the original Master System game.

"Improving an emulated game is pretty hard and I don't think people have done it a lot. That was a more interesting problem than just converting all of the code. I thought it was more interesting to build this thing where I could improve an emulated game. I don't think that's been done before," says Cornut. "It sort of emulation-based, but it's hybrid and weird. The game is mixture of hacking the original ROM and hacking the emulator."

The hacking had to happen because the original Wonder Boy: The Dragon's Trap was built to certain specifications. To run the game on modern systems, a number of changes had to be made. The game had to be moved from 30hz to 60hz. Since most televisions are widescreen, Wonder Boy shifted to a widescreen presentation, which also required a rework of the game's levels, since they were designed to be viewed on older televisions with 4:3 aspect ratio. Further, LizardCube had to develop a level editor for the classic and modern versions of the game, because both had to work.

"I had a proof-of-concept, but I was sure it was going to fall apart at some point."

The modern Wonder Boy presentation is actually an additional layer on top of the original game. LizardCube added whole animation cycles and original sound effects that weren't accounted for in the Master System release. "The original game didn't have animation," explains Cornut, getting technical for a bit. "With a character jumping, there was no different animation going from ground to air. The high-level system is adding a layer while maintaining the [state of the original game]. There are very few sound effects in the original game. By reading the state, when the game wants to play an attack sound effect, we play a different one based on the weapon and the character. We're expanding on the game."

"Halfway through, I had no idea if it would work," Cornut laughs. "I had a proof-of-concept, but I was sure it was going to fall apart at some point." One of the remake's crowning features, the ability to switch between the classic presentation and remastered version, was simply a matter of the team needing to be able to make sure any changes still worked in the original 8-bit version.

"Initially, I had the 8-bit version running and we just started replacing things. It was only a few months in where I added the ability to restore the 8-bit version, just because I needed to compare," says Cornut. "Doing the smooth switch, everybody loved it. It improved the new game. We didn't really think about it. We might've had it in the menu. Then we realized how cool it was and we made sure you could do it any time."

What's Next For Omar Cornut

Wonder Boy: The Dragon's Trap is out, having launched on PlayStation 4, Xbox One, and Nintendo Switch on April 17, 2017. The PC version of the game is coming at a later undisclosed date, as the team is still working on the port. Like any game release, these are the early days. LizardCube has to see if the game's profitable and hammer out any of the bugs players find.

When I ask Cornut what's next, he seems to be a bit taken aback by the question. "I don't know actually. The tech, this is like version 1," he says. "Part of me wants to make new games. The creative me is sort of ashamed to be making remasters. The technical me finds the process very interesting. If we were to make another remake, we need to find something that first we love enough and then this game has to be something we can get the license for. I wouldn't mind remaking The Legend of Zelda, but Nintendo is never going to let us."

"I wouldn't mind remaking The Legend of Zelda, but Nintendo is never going to let us."

"It would have to be a game that would resonate enough with people to be viable as a business. Wonder Boy checked off all those things. The nostalgia factor is really high. For many who had a [Sega Master System], this game was it. It's a game that's really special for them. Plus, being a Switch launch window title probably really helped in getting attention. There was a lot of luck involved," he tells me.

Cornut says that making games can seem daunting these days, because so many amazing games are coming out. Worse, he's seen development schedules grow and grow for some games. Cornut can't see himself devoting 3 years or more to a project and not knowing if it's going to work out or be profitable. "It's so scary and terrifying to say, 'Oh, I'm going to work on this for three years and in three years it'll be somehow good.' Maybe if we make enough money from Wonder Boy then maybe it'll give me to space to go do that," he laughs.

He points to The Witness as a game that he finds awe-inspiring, as one with a very long dev cycle. "I love The Witness as a player, but it made me sad as a developer. Even though I love this game, even if I was half as smart as those people, I don't know if I want to spend seven years of my life making something like that. People who are really smart also struggle to make games. It's amazing, but it's not amazing enough to make we want to spend seven years of my life to do it. I don't think I could do it, even if I wanted to."

Cornut has another side project that is game-related, but not actually a game. To pull directly from Cornut's official webpage, ImGui is a bloat-free graphical user interface library for C++ aimed at very easily creating debug and content-creation tools for games. C++ is a programming language that's quite common in the gaming industry and ImGui allows neophyte programmers an easier, more visual way to learn and understand the language. He's been working on ImGui since 2014 and maintains a Patreon to continue work on the project. (ImGui's Patreon was suspended as The Dragon's Trap's development entered its final stretch.)

"I would love to work on ImGui. It's the thing I want to do the most, because it's useful to an incredible number of companies," says Cornut when I ask about his side project. "I want to keep it a free software, because I want indies to use it and there are lots of kids programming in C++. They will be the programmers of the future. In every big company, there's at least one team using it. So, I want to keep it free, but I have to convince [companies] to give me money. I think it can happen."

Other than continuing to promote Wonder Boy: The Dragon's Trap, fixing bugs, and finishing the PC version, Omar Cornut's future is relatively open. There's no new project set in stone. Perhaps he'll start another game. Maybe he'll work on ImGui. He could end up working for another company if the opportunity arises. Omar Cornut is a very flexible man and, fittingly, the only real constant of his career has been change.

"If I make a game, it needs to be meaningful in some way," he closes out our interview. "I'm an emotional person and I care about things. It's tough to disconnect from my projects. I think I need to step back and take time to tinker around. Meet people and do game jams. And maybe something will come out of it that I really believe in."