The Bard's Tale Launched the Second Wave of RPGs

HISTORY OF RPGS | Welcome to Skara Brae, and to the future.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

This is the third entry in an ongoing series by Retronauts co-host Jeremy Parish exploring the evolution of the role-playing genre, often with insights from the people who created the games that defined the medium.

When Wizardry landed on Apple II at the end of 1981, it hit with megaton force. Along with Ultima, it defined what computer role-playing games could-and should-be. You'd be hard-pressed to find an early RPG fan or creator who didn't find themselves entranced at some point by Sir-Tech's dungeon-crawler; its meaty mechanics and unforgiving design drew players in, then provided them with enough substance to justify the struggle.

These two role-playing goliaths didn't simply rack up record sales for the era, though. They also helped spark a wave of computer RPGs that drew inspiration from them (or, in many cases, outright imitated them). Along with other foundational efforts like Atari's Adventure, Automated Simulations' Dunjonquest: Temple of Apshai, and Infocom's Zork, Ultima and Wizardry provided designers with all the fundamentals they needed for transforming their own RPG ambitions into digital form.

Past and Future

"Playing Wizardry was so profound," says RPG designer Michael Cranford. "It was like drawing a bunch of connection points for me between gaming in the past and what a computer-moderated experience could be."

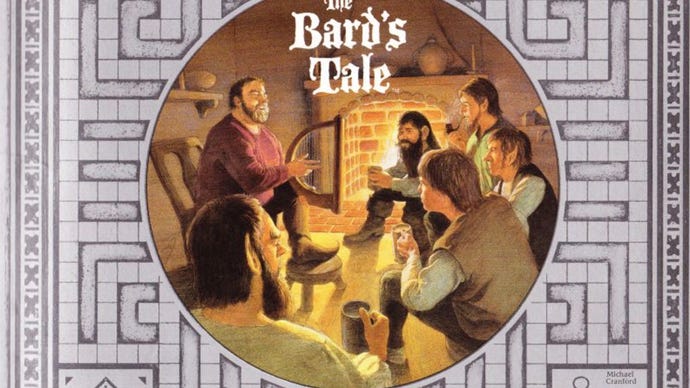

Cranford, whose career has included stints as a writer, programmer, and college professor, would make his own impact on the role-playing genre in 1985. As the lead designer and programmer on the most notable of the second-wave American RPGs, The Bard's Tale, Cranford sought to take computer role-playing to the next level by building on what had come before.

"I was definitely standing on the shoulders of Robert Woodhead there," he admits. "[Wizardry] was a brilliant implementation of a Dungeons & Dragons experience.

"It was so limited in so many ways, but it had a huge impact on me. I loved the game and as I was playing,. I was constantly thinking of ideas. 'I wish I could do this. I wish I could do that.' I was generating a list, because I thought, 'I think I can do this. I think I can actually write something that's like, beyond this.' Then I started wondering if people would want to play this? Would they be intrigued if this had three times the depth of Wizardry? And better graphics?"

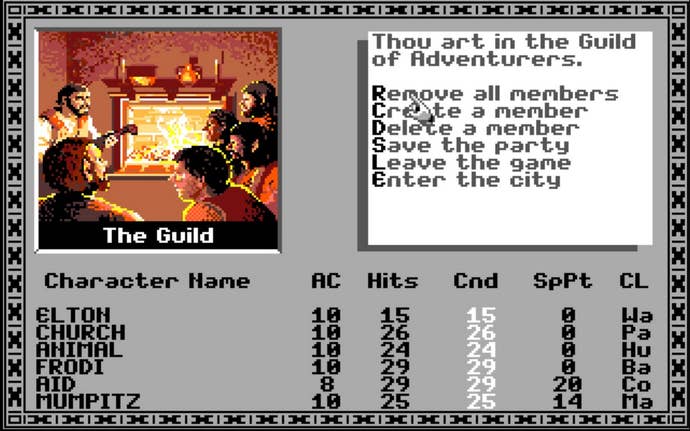

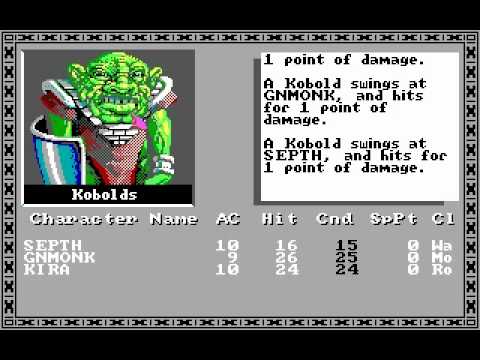

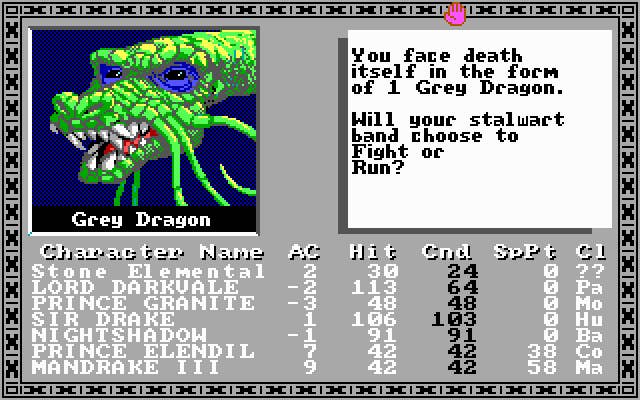

At first glance, The Bard's Tale does indeed owe a tremendous debt to Wizardry. The bulk of the game involves traveling through simple first-person dungeons, battling hordes of random monsters with a six-member party of warriors. Even the screen format looks much the same, with party information appearing as a permanent fixture below a windowed dungeon view and text display.

"I was constantly thinking of ideas. 'I wish I could do this. I wish I could do that.' I was generating a list, because I thought, 'I think I can do this. I think I can actually write something that's like, beyond this.'"

At the same time, Cranford created a game experience that went far beyond the strict dungeon-crawling of Wizardry. While it lacked Ultima's emphasis on exploring a world and interrogating non-player characters with keywords, it nevertheless presented a virtual space that consisted of more than just a dungeon and a menu for dealing with essential tasks in town. The Bard's Tale broke its dungeon into multiple pieces, all scattered across a town called Skara Brae.

Skara Brae itself proved to be a setting every bit as rich as the dungeon's depths-even more so, in some respects. Players navigated the city as they would a dungeon. It sprawled across a 30x30 grid that demanded to be mapped by hand, just the same as the mazes below the surface. Adventurers didn't need to contend with random monster mobs in the city streets, of course, as Skara Brae existed as a sort of safe version of the labyrinthine depths. Yet it nevertheless played a significant part in the quest: The fragmented dungeon could only be accessed from different points within the city, and each entrance was hidden behind a series of cryptic riddles and oblique tasks. In other words, The Bard's Tale managed to take the Wizardry format and integrate a degree of Ultima-esque world-building and narrative that Sir-Tech's impressive RPG had lacked.

They were critical [to the quest], and I'd have guys like Brian Fargo studying the drawing. They're like, 'What's that right there? What's that thing we're seeing peeking out behind that rock right there?'

Cranford (along with his collaborators on The Bard's Tale, which included such future video game luminaries as Brian Fargo and Lawrence Holland) put together a game that looked a lot prettier than Wizardry, as well. The wire frame dungeons and crude monster illustrations of earlier dungeon crawlers here solidified into more concrete imagery. Labyrinths now consisted of colored walls with unique "event" spaces rendered in even greater detail. Above ground, Skara Brae's brick walls gave way to meticulously illustrated shop and pub interiors. Even the randomly encountered monsters didn't simply look nicer than in previous RPGs, they actually displayed simple animations.

The Bard's Tale became an instant hit, and its graphical finesse accounted for much of its popular acclaim. That aspect of the game had come naturally to Cranford, a capable illustrator. TIndeed, the elaborate visuals and intricate puzzles of Skara Brae were-typically for RPG developers in this era-elements Cranford had carried over intuitively from the tabletop gaming sessions he had run with his friends and collaborators.

Visions

"I wasn't told how to do all of this," he says. "To me, it was like, I'm going to make this a story. It's going to be an adventure. It's going to be like a great novel. It's going to have a visual component to it. I was an artist, so I used really elaborate drawings. I fit things into them, so it wasn't just window dressing. They were critical [to the quest], and I'd have guys like Brian Fargo studying the drawing. They're like, 'What's that right there? What's that thing we're seeing peeking out behind that rock right there?' Some of that stuff was relevant, and with some of it I was just kind of messing with them, because I knew they would scrutinize everything. They loved that stuff. It became a lot of fun developing these complex visual puzzle-solving adventures.

"Combat was just sort of the flavoring that tied everything together, rather than a lot of these canned campaigns which were all just fight after fight after fight after fight. Mine were all more about a story. There were a lot of NPCs in my adventures that would come to life and help you and provide special clues or keys to getting past certain things."

In a sense, The Bard's Tale straddled the line between RPG and the burgeoning graphical adventure genre, which had begun to explode in popularity thanks to the likes of Sierra On-Line hit King's Quest. The graphical adventure wasn't too far removed from RPGs, especially in those early days. After all, that genre had emerged as an offshoot of the text adventure, which experienced its defining work in Infocom's Zork. In many respects, Zork amounted to an alternate interpretation of tabletop RPGs, one that emphasized the narrative and puzzle dungeons over combat and hunting for experience points. That The Bard's Tale should echo graphical adventures seemed only natural-another indication of the thin and often arbitrary lines that define genres.

Cranford unsurprisingly acknowledges Zork's influence on his own work. "I played Zork, and that was the kind of gaming I liked to do, no question," he says. "There was combat in there, but it was definitely intentional and not just, 'I'm putting three orcs here and five goblins here.'"

Besides his love of gaming and his passion for drawing, the third pillar of Cranford's contributions to The Bard's Tale turned out to be his knack for programming. While Wizardry had been a landmark work, it (and its first three sequels) ultimately ended up being hampered by their use of high-level programming languages. Wizardry relied on Pascal and BASIC, which made them highly portable across multiple platforms, but it also worked to their detriment by crimping their size and reducing their speed. On systems as limited as the Apple II or Commodore 64, the resources required to run these advanced programming languages in the background cut into system memory and disk storage space that could have been used for additional dungeon levels, extra monsters, or prettier graphics.

"I knew that because [Woodhead] had written Wizardry in Pascal, he had this big runtime engine," recalls Cranford. "I was thinking all the overhead from that is what made it so slow and so limited. I'm a 6502 assembly language developer, and [that meant I would have] five times the space he had, plus the efficiency of machine code. I knew my game was going to be a lot faster, and I had more system resources that I could put in there."

"My frustration [with tabletop gaming] was that it was so unstructured."

Compare Wizardry and The Bard's Tale running side by side on the same machine, and the difference becomes obvious. Cranford's use of low-level machine code made for a faster, more attractive, more complex adventure. (Though he, too, ran up against the hard limits of those early computers: "I'd get down to where I'd be 15 bytes from the end and I'd have to change monster names to make them shorter so that I could fit in another monster and still have it all there," he says.)

Despite these inevitable logistical struggles, The Bard's Tale stands apart from its predecessors in that Cranford openly embraced the limitations of the available technology. Where the first generation of computers RPGs embodied a struggle by designers to capture as much of the tabletop experience as possible via primitive microcomputers, Cranford leaned into the rudimentary nature of 8-bit computing. To him, PCs offered consistency. Where other designers saw restrictions, Cranford saw the potential for quality control by taking away the fickle human element that made pen-and-paper campaigns such a crapshoot.

Past

"My frustration [with tabletop gaming] was that it was so unstructured," he says. "It wasn't clear what the limits were as to how much you let people get away with. There were so many areas to fudge the play, and that was frustrating. When I finally came to understand that a computer could be involved in this, then the rules are set and the system works the way it works. If you live or you die, that's just the way it is. There was something about it that I felt brought structure into the the thing. It was a perfect synergy between the kinds of gaming I wanted."

Unlike many of his predecessors in the RPG space, such as Richard Garriott and Robert Woodhead, Cranford's experience with computer RPGs came entirely from commercial releases. Being younger than the creators of Ultima, Wizardry, and Zork, he had missed out on the shared computing experiences of the '70s that served as the creative incubators for those games. In a very literal sense, The Bard's Tale belonged to a new generation of games: Ones created by designers shaped by radically different experiences than the ones that had informed the people behind the initial wave of computer RPGs.

Cranford acknowledges the impact this had on his approach to game design. "I hadn't been involved with MUDs," he said. "That probably would have changed my approach. My approach was more like the solo adventure idea: Me playing Dungeons & Dragons and not needing anybody else because the system would be the dungeon master. Of individuals being able to game on their own rather than having to find a group of people and sit down at a tabletop. If I'd had more of that communal experience, maybe I would have thought differently and had some ideas about multiplayer gaming. But none of that occurred to me.

"There were limitations with the computer, but I knew we could ultimately exceed all those things and build enough intelligence into this that it feels just as natural as tabletop gaming, but structured where [another player] can't do something he's not supposed to. If you have a really good dungeon master, there is something there that it's difficult to capture in any kind of software. But, that's not what I found out there most of the time."

Many of Cranford's ambitions for The Bard's Tale didn't-couldn't-come to fruition with the original game due to the limitations of 8-bit computing. Even so, the city of Skara Brae was something new for the computer role-playing space: A self-contained world that felt almost like a real space. While other computer realms, like Ultima III's Sosaria, enticed players to explore them, they never felt as realized as the hub city at the heart of The Bard's Tale. Players came to know the city and its denizens as they delved into the different underground spaces and returned to gather new information or spend their earnings. It was a reasonable facsimile of the running changes a live dungeon master could impose on a tabletop campaign, if admittedly imperfect.

"It's a trade-off," he acknowledges. "I recognize that you're giving something up here. There is a dynamic quality [to tabletop gaming], but I didn't feel like a lot of the people that I were playing with were great storytellers anyway, so I didn't feel like I was losing a whole lot.

"I could do what I was doing because I felt like my dungeons were really complex and had a lot of cool story elements that would have been almost impossible to fit into an application. But I had hope that it would ultimately get there in time. With the technology we have now, I think you could really almost do everything."

"As I'm developing a game, I'm always thinking, how do I deliver that experience to people? Where they feel like I've just lifted myself to this higher level?"

Still, Cranford feels that The Bard's Tale was heavily defined by the restrictions imposed by early 19'80s technology, and that those boundaries worked to the game's advantage. "I think anytime you have a limited palette to draw on... when you reach the limits of one thing, you can put your back in that corner and focus on other things," he says. "By having very limited graphic and processing capability, you can spend all your time and energy thinking about content, thinking about gameplay, and things like that. If everything's unlimited in the sense of the complexity of the interactivity, processing power, memory, and disk space, it's difficult to know where to invest your time. Next thing you know, you've split your resources in a way which are maybe not going to end up with the best product in the end. You might be a lot better off stopping, saying, 'This is good enough.' I think that the limitations there made it easier to spend time and energy thinking about what was going to make this thing fun.

"When I eventually created Centauri Alliance, I did put more in story elements. But it actually became rather complicated, which is what bogged that project down-the amount of animation and things like that. The Bard's Tale started off really simple, with automated combat and things like that. So it made it easy to get the game done in the first place.

Future

Like many of the RPGs of the '80s, The Bard's Tale hasn't endured to the same degree as simpler properties like Pac-Man or Donkey Kong. An attempt to reboot the series about a decade ago as a comedy RPG went over well with critics, but it failed to resonate with fans who wanted something closer in spirit to the Apple II classics they had grown up with.

Nevertheless, the series has made at least one permanent mark on role-playing thanks to its eponymous warrior-minstrel. The bard in The Bard's Tale wasn't a character but rather a player class that specializesd in spells capable of enhancing other party members in combat. Support class characters were a new concept in computer RPGs at the time, and buff-slinging bards have since become a genre mainstay in everything from the similarly Wizardry-inspired Etrian Odyssey games to the decidedly different Final Fantasy franchise.

Fittingly, the bard class embodied Cranford's creative philosophy toward his game. To his mind, it speaks to the way people tick. "They want to exceed limitations," he says. "They want to be more than they are. They want to be everything that they feel they should be. And technology is our attempt to realize that and we use devices to try to overcome limitations. In a game context, I think why science fiction and fantasy blend together so well is because those things are utilized for the same purpose, to give us the same experience. In my games, I wanted magic to be the center point of the game and I wanted people to have that sense of becoming everything they want to be.

"As I'm developing a game, I'm always thinking, how do I deliver that experience to people? Where they feel like I've just lifted myself to this higher level? So it's kind of a positive realization of an experience of fulfillment and destiny. That's the experience I always wanted to leave people with, because that's the thing I got and I got that from Wizardry, and I wanted to deliver that in my game. You know, helping people to have an experience of being the best they can be, even better than they would have imagined, through their character and their immersion in the game."