Moving Targets: The Rise of Motion Control

From Eurogamer's 2009 archives, Dan Whitehead looks at motion control's triumphs and tragedies over the years.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

In this week of Kinect Sports Rivals' release, we thought we'd republish this Eurogamer piece from June 2009, where Dan Whitehead peers through the curtains of time to the earliest days of the motion control phenomenon and charts the path that led us from Power Glove to Wii MotionPlus. This article was written at what might be considered the peak of the motion control craze, so five years later some of its surety about the future of the form feels a little optimistic, albeit understandable at the time. Perhaps the same will be true of VR five years hence? In the meantime...

"Love's got the world in motion," trilled New Order, but even a majestically awkward John Barnes rap couldn't change the fact that we were all sadly misinformed. It was our old pal games, not soppy old love, that eventually got the world in motion. Specifically, it was Nintendo's Wii Sports, making us throw our gaming hands in the air and wave them like we just didn't care, and with the MotionPlus add-on now available, those who doggedly claimed hand-waggling control was just a temporary fad are biting into a stale sandwich of wrong.

After E3 2009, it's no longer just Nintendo throwing money at motion control and looking for new ways to turn our entire bodies into surrogate joypads. Sony unveiled its suggestively shaped take on the Wii Remote, while Microsoft gave us a glimpse into a terrifying interactive future where sallow-faced digital children will invite us to molest fish using virtual fingers. Far from being a new trend, however, the move to motion control has been a holy grail that the games industry has chased for the better part of two decades. And it was, rather fittingly, Nintendo that got our arms twitching back in 1989 with the legendary Power Glove for the NES.

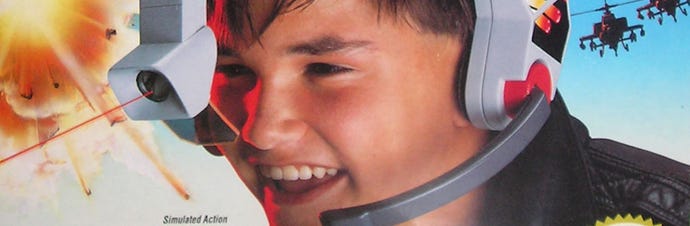

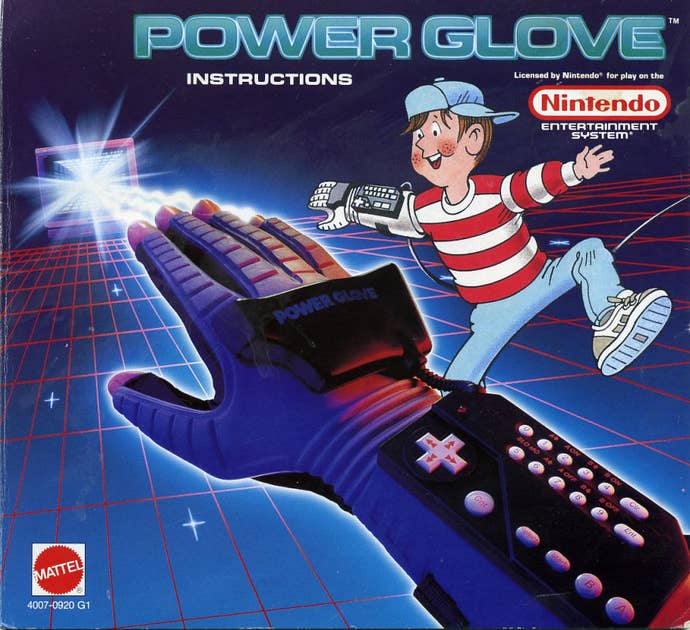

This fashionable accessory, manufactured by Mattel, not only translated hand movements and finger curls into on-screen action, it also featured a wrist-mounted control panel that allowed gamers to program their own button configurations. Even more thrillingly for the youth of the day, it was based on actual technology used by NASA -- the VPL Dataglove.

The Power Glove was based on actual technology used by NASA -- the VPL Dataglove. Of course, there was something of a technical gulf between the expensive devices used by a pioneering space agency and the plastic effort sold in toy shops.

Of course, there was inevitably something of a technical gulf between the enormously expensive input devices being used in simulations by a pioneering space agency and the plastic effort being sold in toy shops. Where the Dataglove used optical fibres to detect the pitch, yaw and roll of the user's hand, recognising 256 increments of finger twitch, the home version could only tell if you were rolling your hand from side to side and was limited by the meagre NES memory to accept only four levels of finger movement.

This didn't stop Nintendo marketing the Power Glove as the peripheral that would change gaming forever. It went as far as making it a central plot point in The Wizard, an utterly shameless Nintendo-endorsed movie which featured Wonder Years star Fred Savage taking his autistic video game whizz brother cross-country to participate in a gaming tournament. Their Rain Man Jr quest is almost halted by the interference of Lucas Barton, a scheming rival who dazzles his parochial foes with the awesome Power Glove. "I love the Power Glove. It's so bad!" he famously exclaimed after showcasing his mad skillz. While he was using the late eighties street slang where bad meant good, he was ultimately proven correct by the more enduring dictionary definition in which bad just means rubbish.

The Power Glove may have looked awesome, but it just wasn't much good as a video game controller. Technically compatible with every NES game, only a few titles bothered to make a feature of it. The self-explanatory Super Glove Ball was the sole game to be explicitly linked to the glove, with obscure beat-'em-up Bad Street Brawler offering some exclusive moves to those wearing the contraption. There was no getting away from the fact that most gamers simply ended up using the wrist-mounted joypad for the fiddly bits and, inevitably, migrating back to the proper joypad once they'd had enough of dressing up like Tron's idiot cousin.

But the ill-fated Power Glove wasn't the only motion controller tempting NES owners in 1989. As players flexed and thrusted their fists in frustration, Brøderbund Software was claiming it had "the most amazing accessory in video game history" -- a controller that you didn't even need to touch.

Brøderbund's U-Force was somehow even more bizarre than the Power Glove, and even more likely to make you look like a tit. Using a pair of infra-red sensors, set at right angles to each other, it attempted to read your hand movements as you gesticulated between them. Needless to say, even TV ads drenched in dry ice couldn't mask the fact that the readable area was far too small, requiring players to keep their movements to a space roughly the size of a loaf of bread, As with the Power Glove everyone soon realised that it was far simpler -- and much more effective -- to stick with those old-fashioned d-pads and buttons, and the U-Force (U-U-U-Force!) swiftly sank into justifiable obscurity.

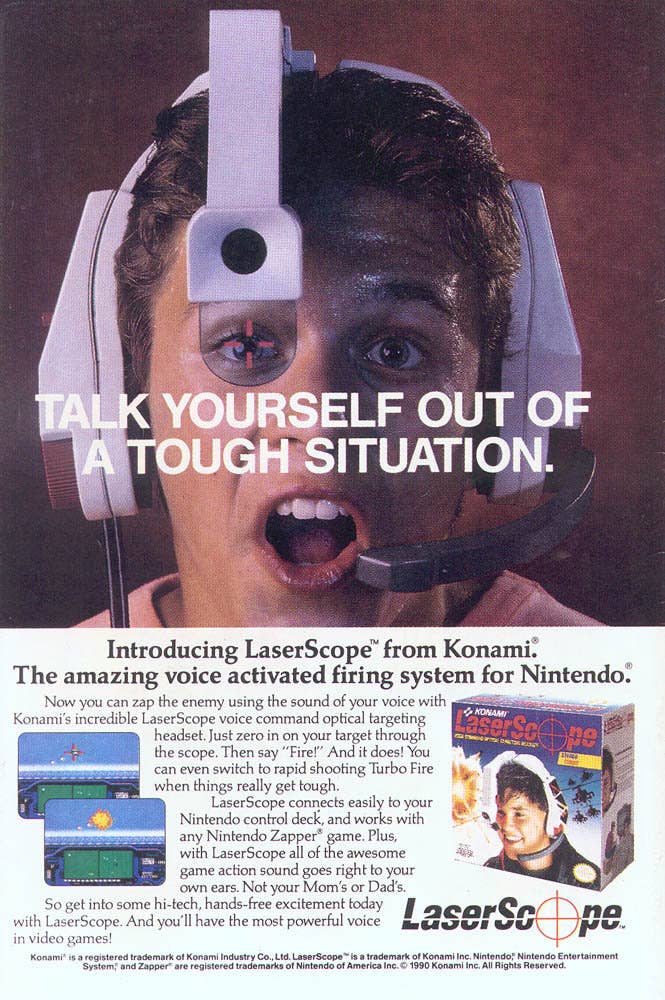

These twin failures didn't stop Konami from taking a spin on the motion control carousel a few years later. In 1991 it tried to sell a now-wary audience of NES owners on the merits of the LaserScope. Admittedly, this bit of kit had at least one advantage -- it was basically a lightgun shaped like a headset, and it actually worked as advertised. It was compatible with all the same games as the NES Zapper, and came with Laser Invasion, a rather limp Operation Wolf knock-off.

With the LaserScope perched atop your head, an eyepiece showed you where you were aiming. You simply had to look at the target. Unfortunately, what came next immediately placed the LaserScope in the same awkward company as its predecessors. Whenever you wanted to actually shoot what you were looking at, you had to shout "Fire!" into the attached microphone. As with the aiming, it did at least work, but the unavoidable embarrassment attached to the hardware meant that few players were keen on bobbling their heads around like Twiki and bellowing "Fire fire fire fire fire" for hours on end. With only the eminently punchable Johnny Arcade to extol its virtues, the LaserScope joined the Power Glove and U-Force in the rapidly growing pile of useless plastic crap that NES owners had shamefully accumulated.

With early Nintendo fans duly turned off the notion of motion control for another three hardware generations, the next bite at the cherry came from arch-rival SEGA, and it was to be a peripheral which would pretty much kill motion-sensing in games for another decade.

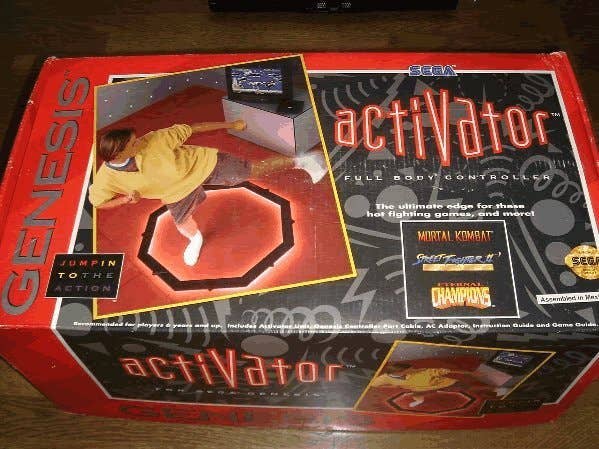

The SEGA Activator was arguably the most misguided of all motion accessories, both clumsy in design and appallingly inept in execution. Produced for the Megadrive in 1994, it took the form of a plastic octagonal ring which had to be assembled piece by piece. Infra red beams rose up from each section, and breaking these beams with your extremities sent different control signals to the console. To "press start", for example, you had to stick both arms out behind you.

Right from the start, the project was plagued by obvious problems. The flimsy plastic ring was easily kicked while playing, while the beams struggled to cope with any variation in the ceiling above, whether it be a lampshade or uneven coat of plaster. The ring had to be put together in exactly the same sequence each time, and had to be recalibrated even when changing cartridges. "Feel free to consider yourself a pioneer on the interactive frontier," gushed the instructional video before sternly detailing the many things that you absolutely must not do in order to keep the temperamental gadget working.

Most damagingly, the Activator was awful for playing games -- doubly so, since it was inexplicably marketed as being ideal for fighting games. Players soon found the reality was quite the opposite, since it was virtually impossible to perform any combo moves. The directional controls were mapped to the front, rear and sides of the ring, with the face buttons in-between. There was simply no way to go left, up-left, up in one fluid motion. If a limb or pants leg passed over an intervening beam, the game got horribly confused while players strained uncomfortably to keep their balance. Essentially little more than a crude dance mat made of invisible light, the Activator sank without trace.

It would be nine years before anything resembling motion control would be taken seriously again, but the next attempt would finally prove a roaring success. While it was Nintendo that pioneered motion control, and later made it ubiquitous, it was Sony that first managed to turn it into a commercially and critically successful product.

In the end, cracking the motion control nut required nothing more sophisticated than a USB webcam coupled with simple yet appealing software -- not so much a lesson Nintendo took on board, but a reminder that cheap technology could often be creatively repurposed for wild profit. Supported by over 30 games, some would argue that the EyeToy isn't even a motion-sensing device in the strictest technical sense, merely a method of gesture recognition, but there's no denying that it allowed players to play games with their whole bodies rather than just fingers and thumbs, and also warmed up the casual market that would make the Wii such a smash hit.

Of course, that didn't stop some companies from falling back on the old standards of intrusive gadgetry and weak software. The Gametrak system, released for PS2 and Xbox in 2004, tried to sell gamers on one-to-one recreation of arm movements using string.

Supposedly inspired by a retractable hotel room washing line, Gametrak used tension cables on spools for its effect. These cables passed through small analogue joints and clipped onto fingerless gloves worn by the player, so as they moved their arms the device was able to work out the in-game positioning by how much string was spooled out, and in which direction the strings were being tugged. Simple, but surprisingly effective.

Despite making the player look a bit like a daft puppet, the Gametrak actually worked fairly well, with the bundled fighting game Dark Wind offering a basic yet compelling showcase for the benefits of throwing virtual punches. Real World Golf was also produced for the system, reaching the Top 10 in UK sales and spawning a sequel in 2007, but Gametrak as a viable alternative controller never caught on with the public. Titles such as Real World Basketball were promised but never materialised. The company responsible, In2Games, eventually announced the Gametrak Freedom motion-sensing wand in 2008 and also foisted the grotty Wii rip-off RealPlay series on us, which, if nothing else, at least inspired Ellie to one of her most memorable expressions of critical dismay.

The most obvious reason for Gametrak's long-term limp performance was that by the end of 2006 the general public was rather more enamored with a different take on motion control, as the Wii finally burst onto the scene.

According to legend, development on the motion-sensing technology at the heart of the Wii remote began as early as 2001, with Gyration Inc -- a developer of wireless computer mice -- and Bridge Design tasked by Nintendo with incorporating movement control into an appealing video game peripheral. Miyamoto apparently brought in mobile phones for inspiration, and early designs included a breakaway joypad with a detachable motion sensor, and one with an analogue stick and DS-style touch-screen. In the end, the company settled on something that looked more like a TV remote, with the optional nunchuk for more intricate control.

Rather than try to convince people to play traditional games in a new way, Nintendo decided that the software would sell the hardware, rather than the other way around.

Rumors persist that this research was originally geared towards producing a motion-sensing controller for the GameCube, an idea seemingly supported by the now-defunct Factor 5 development studio claiming to have worked on a prototype of Star Wars: Rogue Squadron using a rudimentary version of the Wii remote. Such rumors no doubt delight those who decry the Wii as "GameCube 1.5", but that rather misses the point. With motion control a reality, Nintendo realised it didn't need to keep fighting against Sony and Microsoft in an increasingly costly hardware war of attrition.

It had the technology, but without the right software there was every chance that the Wii could go the way of the Power Glove if people didn't take to the concept. Rather than try to convince people to play traditional games in a new way, Nintendo decided that the software would sell the hardware, rather than the other way around.

Animal Crossing designer Katsuya Eguchi was given the job of creating a game that would not only instruct people in how to use the Wii remote, but provide a selling point for the system itself and encourage people to play it daily.

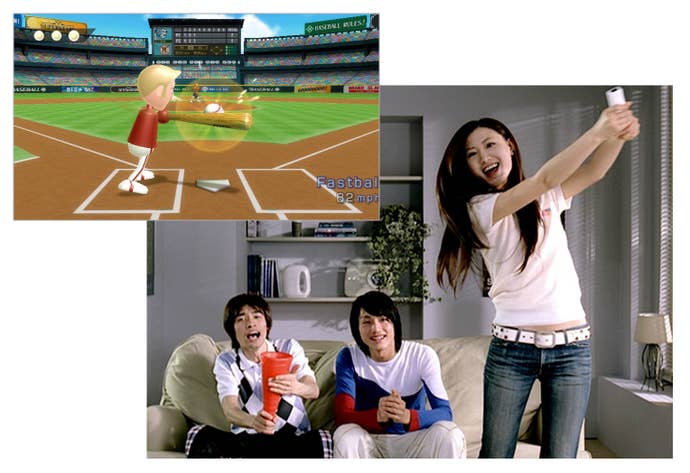

Simplicity was key, and sport was chosen as the most instinctive way for players around the world to ease into the idea of motion control. Wii Sports: Tennis was announced first, prior to E3 in 2006, swiftly followed by the news that it would be part of a branded series. Wii Sports: Golf and Wii Sports: Baseball were added to the line-up, with the latter only featuring basic batting. At E3, Wii Sports: Tennis was famously demonstrated on-stage by Miyamoto, Satoru Iwata, Reggie Fils-Aime and a competition winner, Scott Dyer, and many cocked an eyebrow at how simple the gameplay was, with the only input being the swing of the racquet. At the Nintendo World event later that year, boxing and bowling were added to the official line-up along with the news that the Wii Sports package would be given away free with the console -- in Europe and America at least.

It was a shrewd move, hardware and software in the sort of commercially successful symbiosis that hadn't been seen since Mario came bundled with the SNES. Each console sold helped Wii Sports on its way to becoming the most successful video game in history, and a new audience of gamers -- with no lifelong attachment to joypads -- embraced the world of motion control as a fun and communal experience.

While it will probably never completely overshadow traditional joypad gaming, there's little doubt that motion control isn't going anywhere any time soon. Wii Sports Resort and MotionPlus can only strengthen Nintendo's hold over the casual living rooms of the world, and Sony's bulbous sex-wand and Microsoft's Kinect are strong indicators of the direction gaming is heading towards.

No doubt there'll be some more U-Forces and Activators along the way, but with technology that can finally deliver on the technological promise, and games that can be controlled by brainwaves already a virtual reality, it shouldn't come as too much of a surprise if one day we find ourselves kicking up a stink in some futuristic nursing home with our crotchety insistence that things were simpler in the days when games were controlled with plastic buttons and tiny joysticks.