How the Ultima Trilogy Took a Genre from Tabletop to Hi-Tech

HISTORY OF RPGS | In Part One of our new monthly series, Lord British shares his perspectives on the process of bringing pen-and-paper RPGs into the digital realm.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

This is the first entry in an ongoing series in which Retronauts co-host Jeremy Parish hopes to explore the evolution of the role-playing genre, often with insights from the people who created the games that defined the medium.

What is a role-playing game? Perhaps no other question in video gaming has launched quite so many forum debates over semantics. Fans of Final Fantasy sneer at the notion that the Zelda games should be classified as RPGs, while in turn hardcore PC gaming grognards shake their head in disgust at the superficiality of Final Fantasy’s approach to RPG concepts. Is Dark Souls an RPG? Is Castlevania? Call of Duty multiplayer has experience levels and character classes—is that an RPG? Can any computer-based experience actually be an RPG, when you get down to it?

We can at least refer to an objective standard for defining the RPG: Dungeons & Dragons, the tabletop gaming phenomenon that debuted in 1974 and served as the inflection point for the genre as a whole. D&D adapted tabletop war gaming into a modular format focused around small teams of adventurers. It introduced the standards that continue to define RPGs more than four decades later: hit points, character classes, the chimerical combination of rules and luck that drive combat, and finally the need for some sort of narrative framework to motivate players. Computer and console RPGs attempt to distill these elements into combinations that work within the constraints of digital media, remaking the act of role-playing in a format where the human-driven element—the game master guiding the players’ quest—is replaced by a CPU as a matter of necessity.

Every RPG designer has a different idea of what it means to transform the tabletop experience into something that fits within the boundaries of a computer. So, too, do players… which is where those semantic debates come in.

Over the coming months, this series will explore the history and evolution of computer and console RPGs by documenting the milestones of the genre. The goal: To understand what it means to be an “RPG,” precisely, and how different designers have reinterpreted the concepts that D&D laid down. When possible, we’ve spoken to the people behind these landmark games to better appreciate the reasons they made the choices they did, and to better understand their relationship with the genre. In that light, it makes sense to kick things off with the first commercial video game release to capture the essence of D&D: Ultima, the brainchild of designer Richard Garriott.

Pioneering Play

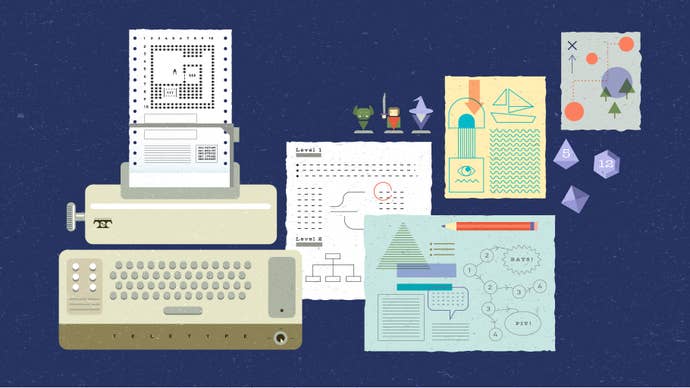

"There are only a few people that go back in the [games] industry further than I do," muses Portalarium creative director Richard Garriott. "I go back to before personal computers. I wrote my first games on a teletype, with strips of paper tape as the memory and an electromechanical typewriter as the input device."

Garriott doesn't necessarily look like someone who helped revolutionize video games back in the medium's earliest days. Compared to most computer game pioneers of the ’70s, he appears far too young to have launched one of the most formative and influential computer games ever made. Yet he designed his first game in 1977. His breakout hit, Ultima, launched a few years later, right as America was collectively calling in sick to work due to Pac-Man Fever. There's no denying the influence of Garriott's work over the past four decades.

Of course, there's a reason for Garriott's relatively youthful appearance: He was still a teenager when he made his RPG debut. His prodigious aptitude for multiple disciplines—design, programming, and storytelling—blossomed against a backdrop of the fantasy genre's explosive popularity in the U.S. during the 1970s. All these factors came together to inspire Ultima.

As the creative visionary behind Ultima, Garriott can arguably claim responsibility for more medium-defining works than any other game designer outside of Nintendo's Shigeru Miyamoto. Along with Sir-Tech's Wizardry: Proving Grounds of the Mad Overlord and Atari's Adventure, Ultima laid the groundwork for how role-playing games should work on personal computers—and, eventually, on consoles. The influence of the Ultima games, and 1983's Ultima 3: Exodus in particular, reached far beyond the U.S. market. They guided a generation of Japanese and European designers as they ventured into the role-playing genre with works of their own.

The Ultima concept didn't spring from Garriott's forehead fully formed, of course. Nor did he single-handedly invent the computer RPG. After all, the sort of person who was likely to get heavily into computer programming in the 1970s was also likely to be in love with the formative fantasy genre works that inspired Garriott. He spent several years learning the art of computer game design, building on the earliest examples of the genre. He worked within the limits of the era's impossibly limited technical constraints—sometimes even hashing out his work on systems that lacked a screen, as with the aforementioned teletype device.

"I wrote a series of games while I was in high school [on] that teletype," he says, "and at the same time, I was introduced to two other very formative events. One was reading Lord of the Rings, and the other one was the publication of the game Dungeons & Dragons. Those three things in my sophomore year mixed together and I wrote a series of… well, they weren't exactly text games like Zork or Adventure. They were 'graphical' in the sense of having asterisks for walls, spaces for corridors, dollar signs for treasure, and this would print out every time you made a move. So if you moved north, you'd actually have to wait for the machine to print a 10x10 grid of text to see what the scene around you looked like from sort of a top-down perspective."

Even working on these primitive proto-RPGs, Garriott proved to be on the right path. The ASCII-based approach he used to present his dungeon layout printouts would become a permanent fixture of gaming a few years later. Rogue, that famous breakthrough in procedurally generated content, used a similar text-based mechanism to create its dense, ever-changing worlds. Rogue was designed to be played on shared mainframes via text-only shared terminals, which themselves were only one step removed from Garriott's teletype.

The Virtual GM

Garriott certainly didn't aspire to create anything as infinitely replayable or deep as Rogue with his teletype-based high school practice projects. Instead, he treated them as if he were a tabletop game master and each teletype project was a self-contained campaign. Even though he admits his early creations were only ever seen by "people who were literally with me at the time," he still approached them with a GM's mindset. Those tentative early works, he says, were inspired not simply by his experiences playing tabletop RPGs, but specifically by his own preferred approach to pen-and-paper games.

"I definitely gravitated toward the game master [role]," Garriott says. "We'd have four or five games going simultaneously. When you went to any one of those tables, you would see some really amazing storytellers, and what all of us felt was that the rules were irrelevant. No one really paid any attention to the die rolls.

"One of the things I realized when I went off to college and came back, the majority of [other players] were worried about die rolls. They'd sit around arguing about, 'I'm up behind you and I'm up on a rock and I have an initiative,' and they'd do complex calculations for a few minutes, roll a die, and… miss. Then, 'Let's start arguing about the calculations again.' I'm going, 'That is not roleplaying.'

"So from the earliest times, I was trying to make a game that was not just about the number-crunching but was asking, 'Can we tell an interactive narrative together?'"

Of course, telling dynamic stories may have been an unreasonable expectation for a teenager creating computer games stored in a few kilobytes of RAM and played on a scroll of printer paper. Yet it's not hard to envision Garriott creating his dungeon maps and simple computer-powered combat as a visible manifestation of the adventures he imagined in his head. His teletype efforts allowed him to create a foundation for the works that would come later, becoming the technical and mechanical underpinnings for games that would revolutionize the concept of video game narratives.

"If you think about the Ultima series," he says, "one of the innovations in most of the Ultimas was the scrolling tile graphic map. Well, if you look at what I was just describing of asterisks for walls and spaces for, spaces for corridors, that was a scrolling tile graphic map. Literally! Physically, on an actual scroll."

"I was trying to make a game that was not just about the number-crunching but was asking, 'Can we tell an interactive narrative together?'"

While these pre-Ultima projects have long since vanished into the digital ether—Garriott even ran a contest a few years back in which fans were asked to explore their vision of what those teletype adventures played like—they served as a bridge between Garriott's pen-and-paper sessions and the sprawling computer worlds he would build throughout the 1980s. Starting out, Garriott didn't feel the need to obfuscate his influences, since his teletype projects were largely made for his own satisfaction. It was only when he shifted to working on personal computers rather than teletype systems that Garriott decided to be slightly less obvious in his love for Dungeons & Dragons.

"I called those [teletype] games D&D 1, D&D 2, D&D 3, and so on," he says. Garriott ultimately wrote 28 of these adventures, and the final entry in this teletype series served as the basis for his move into home computer programming: “When the Apple II came out, I converted the last one I had made—D&D 28—to [Apple]." That reworked project would go on to become Ultima’s prequel, Akalabeth. "In fact, the remark statement at the beginning of the code says 'D&D 28 B'!" he says.

Digital Dungeon

While the idea of creating dozens of tiny games for an almost non-existent audience may strike some as a futile or empty effort, Garriott values the critical discipline he learned during his D&D days. "I was teaching myself to program at the same time [as designing games]," he says. "One of the reasons, I think, for the early success of Ultima was the way I'd rewrite it over and over again to really maximize how much more I could do with each one."

While the Apple II computer proved to be a vastly more capable machine than the teletype that served as D&D's incubator, it was a far cry from modern computers and suffered from many limitations right out of the box. With primitive graphical features, a small amount of RAM, and data storage cramped by the minuscule capacity of 5.25" diskettes, Apple's popular home system demanded clever workarounds for games as ambitious as the ones Garriott had in mind.

Akalabeth: World of Doom, Garriott's graphical remake of D&D 28, arrived in 1979 and entered wider circulation through a larger publisher the following year. That makes it a contemporary of several other pivotal takes on the RPG genre, such as Rogue, Atari's Adventure for 2600, and the official commercial release of Zork. Of all these efforts, Akalabeth was arguably the most ambitious. Fans often refer to Akalabeth as "Ultima Zero," and for good reason. Despite its small scale compared to the actual Ultima games, Akalabeth featured many elements that would appear in the series to come.

Perhaps most remarkably, it depicted its world through two different points of view. Players explored the world through a top-down perspective, a direct extension of Garriott's teletype efforts. But once they entered a dungeon, players were treated to a crude first-person viewpoint via wire frame graphics. While this concept would be expanded on more impressively a year or two later by Sir-Tech when Wizardry arrived, it was quite remarkable at the time. And unlike Wizardry, the first-person perspective amounted to merely one window on the game's world.

The Saga Begins

In a spiritual sense, Akalabeth had more in common with the D&D series than with Ultima. Like those early programming exercises, it was more about getting a sense of things on a technical basis and feeling out the realities of game design in a new medium. It was only after kicking the Apple II's proverbial tires with Akalabeth that Garriott would finally go on to create his first truly notable game, the original Ultima. A much larger adventure than Akalabeth, Ultima required Garriott to make use of all the game making tricks he had learned to that point.

"There was only 64K of RAM in the computer which, when I wrote Akalabeth, I used up," he remembers. "For Ultima, I really wanted more, but the machine didn't have it. How I got around that is… Akalabeth and Ultima 1 were written in BASIC. So I cheated BASIC by saving the same program out multiple times. I changed the end of the program to have call information for new monsters, and I would do a binary load of the back end of a file on top of the running program in memory. I'd have to move the end-of-file markers and do all kinds of unsanctioned modifications of the operating system in order to pull this off! We did that all the time. We were having to hack the system deeply, just to do really basic stuff."

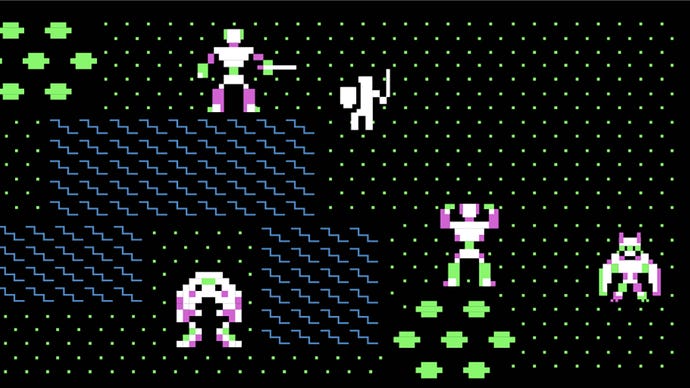

Ultima may have been hacked together behind the scenes, but it truly did capture the feel of a tabletop session like no other computer game before it. In a way, it feels more like a freewheeling, improvisational table top session than its own sequels. Ultima 1 has a real kitchen sink feel to it, mixing pop fantasy with science fiction. It's a game where you can play as a Hobbit (or rather, "Bobbit") who then jumps into a spaceship to battle through shoot 'em up sequences.

The original Ultima contained quite a few sci-fi elements, something that would be winnowed out of the series in short order. By the time Ultima 3: Exodus rolled around in 1983, the Ultima universe had settled into a fairly traditional view of magical medieval fantasy. Exodus' only real nod to sci-fi came in the form of the final boss: Exodus itself was the computer-like offspring of the first two games' villains, and its futuristic nature helped sell its status as an uncanny entity existing at odds with the surrounding world.

The shooter sequences and time travel elements of Ultima 1 and 2 were, in a sense, the last instances of Garriott figuring out what exactly he wanted to do with his work—or as he calls it, the first phase of his career. "The first phase was 'Richard Garriott learns to program and throws everything he can and everything he can do into one game,'" he admits. "So, the first Ultima not only included medieval fantasy and these 2D tile graphic outdoors with 3D dungeons, it also included space flight and literal T.I.E. Fighters. Sorry, George Lucas! And there were land speeders, lightsabers, and blasters. By the time we got to Ultima 2, we included time bandits, cloth maps, and you know, time travel and Jurassic Park dinosaur eras. Basically, everything I could think of, just thrown into one game. If I could make it work, and it was cool in a movie I saw or a book I read, there it was in the game.

"Pretty quickly, though, I got to the point where a few things happened concurrently. One was [realizing] it's really hard to make a game that is both 2D and a 3D. Not only are you coding two engines, but… what do [spells] even mean?” Garriott offers the example of a force field spell. In the 3D, first-person viewpoint of Akalabeth’s dungeons, Garriott says, a force field spell would block the entire corridor. In a top-down 2D viewpoint, though, that same spell would only fill a few blocks of the map, and enemies could walk around it. The fundamental difference between the two perspectives became increasingly difficult to reconcile as Ultima’s mechanics grew in complexity.

"I began to think, 'Okay, I have to decide. I can't do 3D and 2D and outer space. You know, I need to settle in on what I'm doing, physically.' It turns out that tile graphics were my particular area of innovation and specialty, so I stuck with that, because it's the one where I knew I could continue having this kind of leading role. Then I said, okay, that's generally fantasy. If making 3D polygonal stuff had been better, then you know, maybe I'd have made a space game. So I knew it'd be on the ground, and so that put me mostly in a medieval [setting]."

The Third(-ish) Time's the Charm

By the time Exodus debuted in 1983, Garriott had whittled away all the creative dead ends and other cruft of his earliest games. The end result was, after more than half a decade of iteration and experimentation, a brilliant role-playing game that genuinely captured the sensation of playing a massive tabletop campaign. The land of Sosaria, where Exodus transpired, consisted of a vast continent surrounded by huge islands and dotted with both cities and dungeons. Players could effectively travel anywhere they liked from the outset, though deadly monsters proved to be almost as much of an impediment to free-roaming as the cryptic relics and installations that dotted the landscape.

By this point, Garriott had abandoned the first-person dungeon viewpoints in favor of maintaining a consistent top-down look. Even battles played out from above, viewed through a zoomed-in perspective that prefigured the likes of Pools of Radiance and Shining Force. The aerial combat perspective helped set Exodus apart from contemporaries like Wizardry and The Bard's Tale, and not just in a visual sense. Exodus had expanded the player's combat roster from Akalabeth's lone protagonist to a party of four, and the ability to shuffle those heroes around the battlefield helped drive home the fact that you were playing with a virtual group of friends.

Location and positioning became critical factors in combat, too, demanding players and enemies alike move within range of one another in order to perform their actions. Range had existed as an abstraction in Wizardry, where the player's party of six formed up in forward and rear ranks with the back line relying on spells and projectiles in order to attack foes. Here, though, players had full control over their team's arrangement at all times. You could maintain the concept of rear ranks and keep more vulnerable combatants safe from direct attacks, but you could also scatter or reassemble your formation as the situation warranted.

Despite this tremendous improvement to the workings of combat, Exodus was a less conflict-oriented game than its predecessors. The first two Ultimas, and Garriott's preceding projects, emphasized skirmishes with monsters almost as a matter of necessity. "My very first games were just 'go fight stuff,'" says Garriott. "But that was really just a side effect of my learning how to program. Almost immediately, Ultima became filled with characters that immediately had conversations."

While duking it out with the bad guys factored heavily into Exodus, Garriott invested far more time into developing the realm of Sosaria than he had the previous games' worlds. There were more opportunities to interact with non-player characters, and the enigmatic structure of the world demanded players explore, observe, and interact. Mysterious devices called Moon Gates appeared throughout the land. By experimenting with the gates, players would eventually learn that they served as teleporters, with the current phase of Sosaria's twin moons determining the activation of each of gate. Likewise, the battle with final boss Exodus required more than mere dungeon-diving and damage output; success in Exodus requires a fair amount of clue-hunting and puzzle-solving.

While this still didn't bring the game to the point where it perfectly resembled the tabletop social experience simulation Garriott aspired to create, it represented a huge step forward. Exodus' design would serve as the foundation for many of the biggest role-playing franchises to emerge throughout the 1980s and 1990s, especially on the Japanese side of the industry. Eventually, console RPGs would drift far from the principles of design present in Exodus, but even that speaks to the game's influence. Such was its impact that developers stopped taking their cues from Ultima and instead looked to games that had been inspired by Ultima. Ultima-descended RPGs demonstrate a sort of telephone game phenomenon, with latter-day creators building on its principles and strike out in unrelated directions without necessarily having played the original games themselves.

"If I could make it work, and it was cool in a movie I saw or a book I read, there it was in the game."

The Ultima series would continue to evolve beyond Exodus, but those refinements would come largely in the area of narrative and world-building. Garriott and his teammates at Origin Systems more or less had the workings of the genre figured out in Exodus. And while its sequels would be every bit as impactful as Exodus, Garriott looks back at the series' formative years and takes pride in the things he got right early on.

"There are still some things I look back at that we did in those earliest ones that I'm not sure we've really done better since. Even little things like the conversations with my early characters. You could talk to them, and every character knew the answer when you asked them their name, their job, how they're doing. But they all had two more hidden keywords, and those two hidden keywords might be referenced out of what they just said. Like, if [you] ask him his job and he says, 'I'm Joe the fisherman,' fish might be something they might know about. Or it could be that you have no reason to know what the other one might be. It might be 'magic sword'. But unless somebody else in the world, in another area, tells you to go ask Joe the fisherman about the magic sword, there's no way you would know to ask that question of that fisherman.

"It turns out that simple five-state answering of simple questions offered an amazing array of power for me to be able to put very sophisticated stories into the game, as long as I broke it up into tiny little pieces and scattered it into the world. I developed techniques like I would both write out my stories linearly and I would say, you know, you're going to start the game and you're going to go talk to Joe the fisherman, but you don't know about the sword yet. So you have to get further in the game, and you're going to meet this other person who tells you to go back and talk to Joe the fisherman about the magic sword. Now, if I go back, I can find the answer, because I already know where Joe is.

"Then I would take that exact same document, and instead of writing it out linearly, I'd write it out by geography. I'd say, here is town A, town B, town C, town D. What I'd find is a lot of the data of the story, a lot of the advancement of the story, was in [a few specific] towns and virtually nothing was happening in these other towns. So I'd say, 'OK, how can I modify that? Let's move Joe over to this other town. Let's add an intermediate clue that you have to find in some other place.' By analyzing story craft bi-directionally, both how the story flows and how your geographic exploration flows, it allowed me to create quite sophisticated stories, I feel, with quite limited technology. That's a technique that I use to this day."

As it happens, Garriott is quite literal when he talks about carrying his design philosophy forward to the present day. His most recent project, a free-to-start online RPG called Shroud of the Avatar, launched in March 2018 and has already seen several meaningful content updates. Shroud continues the legacy of Garriott's work, specifically channeling Ultima 4: Quest of the Avatar and the influential massively multiplayer RPG Ultima Online. Garriott's vision of the RPG also manifests in the countless modern entries in the genre whose design roots can be traced back in part to the Ultima series. Garriott may not have created the first computer role-playing game, but he arguably created the first to truly matter. Computer RPGs began here.