The Return of a Macintosh Shareware Classic

Ray Dunakin was a star in the days of Mac shareware games. We look back at his World Builder games, and what he's up to now.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

In the heady days of Macintosh shareware gaming, Ray Dunakin was a star. His 1990 world-hopping adventure title Ray's Maze puzzled and delighted Mac gamers the world over, despite it having been made with an early black-and-white Mac program called World Builder, and his later games Another Fine Mess, A Mess O' Trouble, and Twisted! only added to his reputation. But fate conspired to force the games into oblivion as Apple moved the Mac into OS X and then over to Intel processors.

Until now. Marc Khadpe is Ray's biggest fan. He's been the proprietor of the Ray's Maze Page since he created it in 1996. And he's spent the past decade, on and off, rewriting the World Builder engine for OS X.

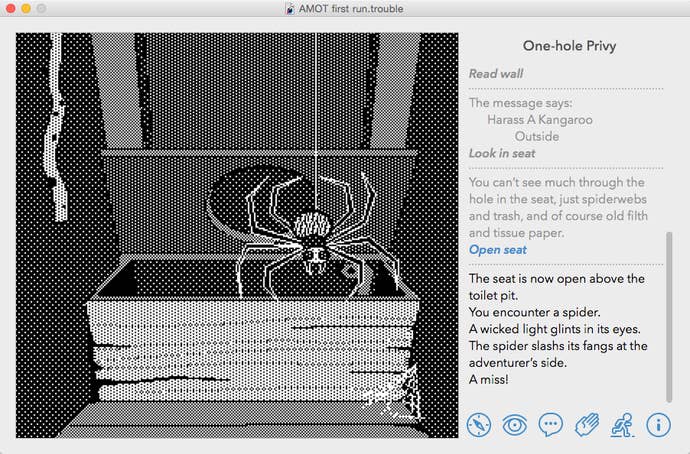

It hasn't been easy. Apple likes to overhaul the innards of its operating system every few years, which has forced Khadpe to rewrite chunks of his new World Builder engine as he's developed it. But a few months ago he finished it, and now Khadpe has reimplemented Ray's third game, A Mess O' Trouble, in this new engine — complete with a fresh lick of paint (though it's still black and white) and a more newbie-friendly interface.

But let's come back to that later. What, for the unaware, is World Builder? Who's this Ray Dunakin guy? And what made his games special?

World Builder was written in 1984 by a graduate economics student called Bill Appleton. He bought a Mac shortly after its January launch that year and taught himself to write code for it, with help from technical manual Inside Macintosh and Apple software evangelist Alain Rossmann — who gave Appleton a copy of the Macintosh assembler.

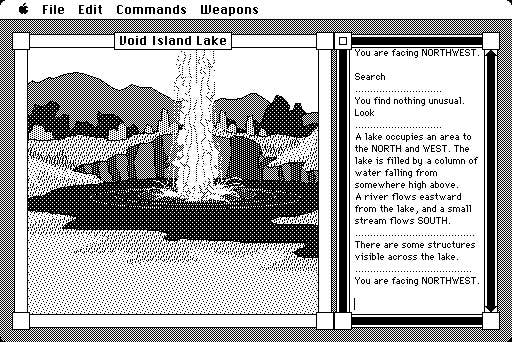

Appleton wanted to write a great adventure game on the Mac. One that would make use of its mouse and graphical menu-driven interface and its relatively high-resolution graphics — 512 by 384 pixels, versus the 320 by 200 pixels offered by IBM PCs and Commodore 64s of the time. Nobody had done anything of the sort except for two Japanese games released around this time — Wingman for NEC PC-8801 and Planet Mephius for FM-7.

In order to write a great adventure game, Appleton felt he needed to write a great authoring tool with which to build it. That became World Builder, which he developed in 1984 and released commercially through Silicon Beach Software in 1986 (one year before Apple's HyperCard, which Cyan later used to make Myst). And the game he made with it, Enchanted Scepters, was released in either late 1984 or early 1985 (I've not yet managed to trace a date), placing it shortly before the first of ICOM Simulations' innovative MacVenture multi-windowed point-and-click adventure games to market.

Enchanted Scepters doesn't look like much today, but to those who played it at the time it was a glimpse of the future. It may have lacked the animation of King's Quest, which Sierra released to IBM's ill-fated PCjr in 1983 and to several other home computers in 1984. But it had then-remarkable sound effects that gave life to its detailed (though somewhat crude and unrefined) graphics. More impressive was that it used a mouse. You could click on doors to open and close them and click on objects to pick them up. Most commands could be executed through clicks or keyboard shortcuts, and you could also do everything through the text prompt — which also included some helpful descriptions of the scene before you.

What's most amazing about Enchanted Scepters is what it represented, however. It was a commercial adventure game made with absolutely no secret tricks or extensions within a tool that ordinary people could buy and use themselves. World Builder let you create or modify commercial-quality adventure games without writing a single line of code. You could even edit Enchanted Scepters, adding more rooms to the 200 it came with or altering its ending or using it as the starting point for your own game. This is at a time when most non-coders were left tinkering with simple BASIC games they copied out of magazines. World Builder followed the "just works" and "for the rest of us" philosophies of the Macintosh to a T.

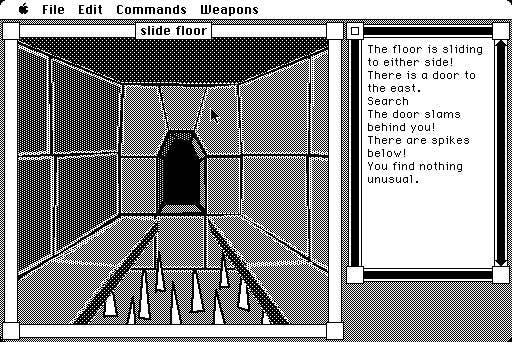

You could draw the "rooms" that the player saw using a mouse and a bunch of simple shapes and pattern fills, then add in objects that the player could interact with and write hints or flavor text to be displayed alongside the graphics. And if you wanted to include extra verbs or more complex interactions, you only needed to learn a very simple if…then (if they click this or type that then do this) scripting language.

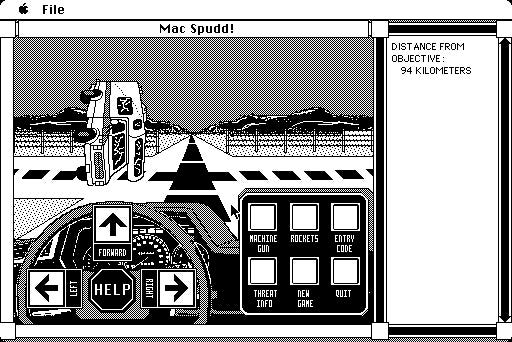

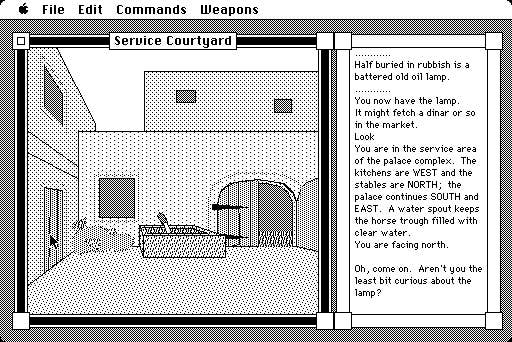

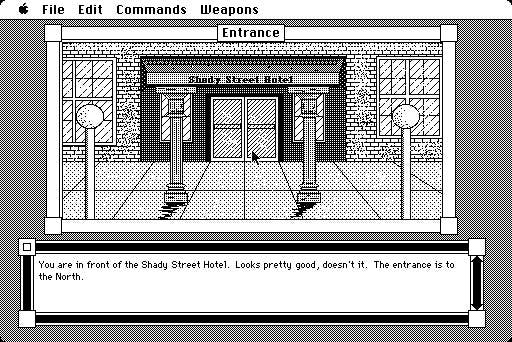

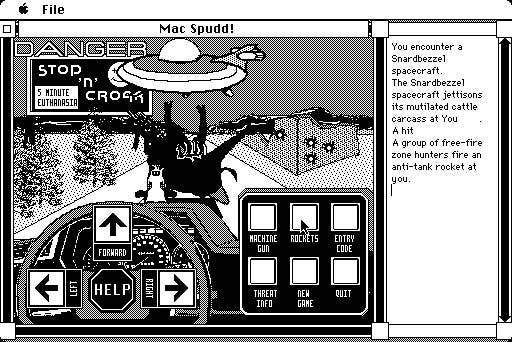

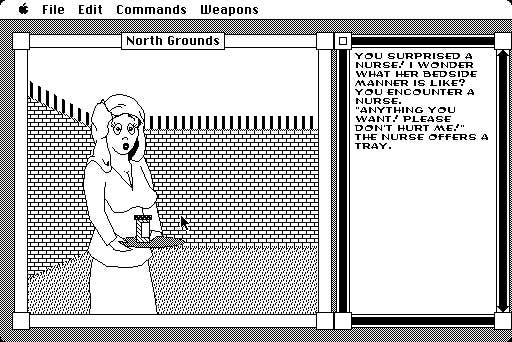

Many Mac users dug into World Builder and shared their creations over America Online or Usenet, with many of the stronger offerings deviating far from the wizards and monsters fantasy of Enchanted Scepters. Mac Spudd! Had you hauling potatoes across post-apocalyptic Idaho in a weaponized car (though you still moved one static screen at a time). The Hotel Caper asked you to rescue Daring Drake and defuse a bomb before it explodes. Sultan's Palace took you and your friend Jake on a misadventure around an Arabian-themed palace and town. And the highly-controversial Psychotic: The Escape had you playing as a dangerous mental patient trying to fight your way out of the asylum.

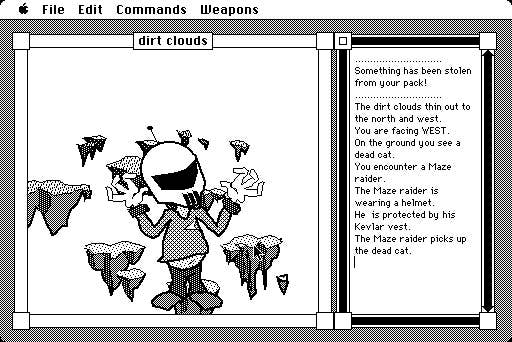

But most renowned of all the World Builder games were those created by Ray Dunakin. His games were bigger, more detailed, better looking, better scripted, and more polished. He came to World Builder a few years after its release, when he and his wife bought a Macintosh SE for their son. He played around with it with his son for a while, then decided to make a full game of his own. That led to Ray's Maze, which follows part-time adventurer "Fearless" Frank Farley in a bewildering, delightful romp through a multi-dimensional maze in which you make lots of Raybucks, find a room filled with heavy polished spheres (known as the ballroom), help the Butthead Trolls of Posteria, and generally get yourself lost as you teleport from world to world. "I like the idea of being able to walk through these jump doors and end up anywhere in time and space without any warning where you were going to be," Ray told me a few months ago.

A sequel called Another Fine Mess followed a year later with more of multi-dimensional maze shenanigans and improved parsing of text input, then another sequel came two years after that. It's this third game, A Mess O' Trouble, that Marc Khadpe chose to revive first. "I wanted to start with a stronger title," he tells me. "Ray’s Maze is fairly primitive compared to Ray’s other games." Whereas Ray's Maze lays heavy on the combat, which in World Builder is kind of rudimentary, Another Fine Mess and A Mess O' Trouble shift the emphasis to story and puzzles. "For someone new to Ray's work," Khadpe explains, these make for a better gaming experience.

Khadpe discovered World Builder in a catalog in around 1990 or so. He was spellbound by the idea of creating your own worlds to explore and puzzles to solve, though he never released anything of his own. In time he went in search of other people's worlds on AOL. "Most of them were pretty short, and a lot of them were crude," he recalls, explaining that World Builder's built-in tools for creating monsters that players could fight became a crutch. World builders could add monsters without writing any code and the monsters would fight according to behaviors defined in the engine. The feature was often used because it was easy, and because the app emphasized it. "But fighting monsters in World Builder gets old fast," Khadpe notes. "The best World Builder games used monsters sparingly or not at all."

Khadpe loves how Ray's games were designed non-linearly. "The first area in A Mess O’ Trouble is a perfect example of Ray’s puzzle design," he says. "The player has to escape from a mineshaft, but there are several possible avenues of escape, including a rubble-filled tunnel and a rope dangling overhead. Instead of the game being constrained such that only the true solution works, the player can actually perform some actions that seem like progress toward an escape, only to eventually find it to be unworkable."

There's always someplace new to visit and something new to do in A Mess O' Trouble. More secrets to find. More worlds to explore. And no fewer than 32 verbs to experiment with — ranging from obvious things such as "look" and "get" to more specific actions such as "listen," "shoot," "sit," and "offer," and even offbeat things such as "lie down," "wave," and "clap." Remarkably, in most situations you can expect many of these verbs to result in a completed action or a fittingly snide remark by the narrator.

World Builder itself includes barely more than a handful of verbs — movement in six directions, look, rest, status, inventory, search, open, close, and some weapon-specific actions. Players of Ray's games had to puzzle out or guess (or look at his world code to find) what verbs to use. This was a huge stumbling block for new players, so in his OS X remake Khadpe has put all of the verbs in menus below the action.

He notes that he went through several iterations on how to display the verbs, ultimately settling on something that balances the clean, minimalist look of the original game with the needs of new players. It's not just verbs, either — Khadpe added context-specific prompts for situations where more information is needed, such as a dial that you drag left and right to enter a combination for a lock.

The response so far has been fantastic, Khadpe tells me. Bit by bit word is spreading among the old fans, who are delighted at the modern update to one of their favorites. Khadpe has yet to hear much from people new to the game, however, and he's curious to see how its non-linear and large world will go down with players more used to linear graphic adventures.

Ray's "thrilled" to see it available again, too. "I think it turned out great and I'm very grateful for the work he put into it," Ray tells me via email. And it's got him thinking about making games again, nearly 15 years after he stopped. Ray would love to repurpose the puzzles and storylines from his cancelled Myst-like adventure Morphworld and the fourth Ray's Maze game A Royal Mess. The problem is that he'd have to create new graphics and redo old graphics to keep the style consistent. "All of this would take a tremendous amount of time, and currently I'm super busy so I don't know when or if I will ever have the time to do that."

In the meantime, Khadpe's working to get the rest of Ray's World Builder games out for OS X with similar enhancements. He hopes to have Ray's Maze and Another Fine Mess on OS X by the summer and at least one of Ray's games on iOS — sans text parser — in the fall. Then, perhaps, if the many other 80s and 90s World Builder creators get on board, we could see a full-blown revival of the first point-and-click adventure game system and the one with arguably the greatest staying power of them all.