Metal Gear: Two Anniversaries, and The Future

Released 10 years apart, Metal Gear side stories Snake's Revenge and Ghost Babel feel worlds apart... yet they may speak volumes about the series' future.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

The Metal Gear series holds a few remarkable distinctions within the video games medium. Those traits seem destined to change soon, but for the moment Konami's stealth action franchise remains one-of-a-kind.

For starters, it features the medium's longest-running continuous video game narrative. No other series has stuck to a single thread of continuity for so long, and especially not a storyline so central to the games themselves. Few currently active game series date back all the way to the 1980s, and those that do either feature standalone plots contained entirely within a single chapter (as in Final Fantasy) or have had connections and timelines grafted forcibly onto them in retrospect (as in The Legend of Zelda). Similarly, no game series besides Metal Gear has remained under the close supervision of its original designer (Hideo Kojima) through the years; even Nintendo's legacy properties have long since seen the likes of Shigeru Miyamoto and Takashi Tezuka step back into supervisory roles. Kojima, on the other hand, remains intimately involved in Metal Gear's story, design, and production.

Nevertheless, Metal Gear is a franchise in the most literal sense, and that means it's licensed out to other creators from time to time. While Kojima has devoted much of his career to the main, numbered entries and major side stories like Peace Walker, Konami has bolstered its bottom line by publishing Metal Gear games handled by other teams and designers as well. Two of those games — Snake's Revenge for NES and Metal Gear Solid for Game Boy Color — celebrated milestone anniversaries this month. Fittingly, both offer clues for how the franchise may be able to carry on once Kojima steps away from Konami.

In and of themselves, you can build a fascinating study in contrasts and comparisons from Snake's Revenge and Metal Gear Solid for Game Boy Color (aka Ghost Babel). Released 10 years apart, the two sit at very different points in the franchise's history and play very differently. Yet both serve the same narrative role in the Metal Gear timeline: They're direct sequels to the original Metal Gear, existing as alternate stories to the true sequel (1990's Metal Gear 2: Solid Snake for MSX/2).

Snake's Revenge came by its role naturally. At the time of its creation, Kojima had directed and designed the first Metal Gear for MSX before moving along to produce the original PC versions of Snatcher. Meanwhile, Konami had gone forward with an NES/Famicom version of Metal Gear, which they produced without the involvement of Kojima. The NES port proved so successful in the U.S. that the publisher quickly commissioned a sequel — again, without bringing Kojima into the loop, most likely because this follow-up would be strictly for the NES, and Kojima only had experience with computers like the MSX and PC-8801.

In other words, Snake's Revenge became an alternate Metal Gear sequel because at the time there was no "legitimate" sequel. In fact, Metal Gear 2 came into being as a direct result of Snake's Revenge; a popular anecdote tells that one of the designers on the NES sequel broke news of the project to Kojima and encouraged him to create his own follow-up.

Those two sequels, released mere months apart, couldn't have been more different despite the similarity of certain plot and mechanical beats. Perhaps the key to their divergent design rests in the fact that Metal Gear 2 was designed exclusively for a Japanese audience — it was one of the last big releases for the MSX/2, which never found footing outside of Japan — whereas Snake's Revenge was aimed at American audiences. It didn't simply target overseas fans; it was never released in Japanese, despite being designed internally at Konami's Kobe headquarters.

Thanks to its semi-official status and misfit nature, Snake's Revenge offers a bizarre window into the Metal Gear universe. The plot largely recycles that of the original game, with the plans for mobile nuclear platform Metal Gear having fallen into the wrong hands and Solid Snake tasked with rescuing various hostages en route to preventing the construction of the doomsday weapon. By comparison, Metal Gear 2 presented a far more involved and convoluted story in which the titular weapon took something of a back seat to a scheme involving a synthetic bacteria that threatened to destroy the world's oil reserves. Snake's Revenge advances its story through radio communications, but these happen sporadically and offer little real detail compared to the lengthy conversations of Metal Gear 2, which touch on the horrors of war, the particulars of Snake's equipment, and the drive for soldiers to find purpose in conflict.

Really, about the only thing the two games have in common is the way both resurrect the first game's villain, Big Boss, to be revealed as the mastermind behind each plot. Even those revelations play out quite differently; in Kojima's version, Snake overcomes impossible odds to defeat Big Boss with improvised weapons after abandoning his gear for a deadly hand-to-hand duel with former comrade Grey Fox. In Snake's Revenge, Big Boss adopts the form of a cackling cyborg best taken down with a rocket launcher.

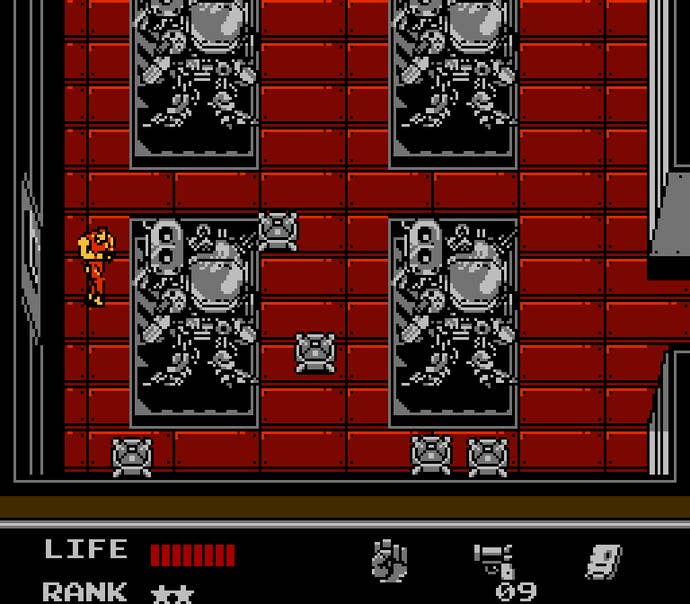

Snake's Revenge offers even more offbeat takes on Metal Gear conventions than that. The adventure breaks down into a far more linear format than the original game, with each area of the enemy base largely taking on a self-contained structure; once you've cleared out one area, you advance to the next through a connecting sequence. It's these interstitial moments that really break from anything ever seen elsewhere in the franchise: They play out as side-scrolling platforming challenges in which Snake runs, jumps, stabs, and shoots enemies. It's pretty weird, especially given the future evolution of the franchise, not to mention painfully clumsy.

And yet, it's hard to call Snake's Revenge a bad game. Certainly it seems awkward given the way Metal Gear would unfold through later sequels, but it clearly was developed in good faith by a capable team. It's wildly unbalanced and sometimes thoughtlessly designed — many level layouts in both the top-down stealth and the b sequences make it difficult to avoid detection without memorizing the starting position of enemies — and yet despite its failings, you can see it straining to uphold the Metal Gear spirit. Stealth plays a key role in this game, as it does in any other entry of the franchise, and while it may be harder to avoid detection due to poor enemy placement, Snake nevertheless gets about quietly. One of the first tools you acquire is a silencer, creating player choice: Do you rely on weaker weapons like knives and silenced pistols, or do you go in guns literally blazing with high-calibre rifles that do more damage but expose you to greater danger? Even the dreadful side-scrolling sequences emphasize stealth. You must crawl up to foes and take them out unseen or risk being overwhelmed by a flood of enemy soldiers. It's poorly done, but nevertheless you get the idea.

The key to understanding Snake's Revenge is not to see it as a sequel to Metal Gear, but very specifically as the sequel to the NES version of Metal Gear. The MSX game underwent a lot of changes in its conversion to Nintendo's console, picking up a number of glitches (mostly due to the rearranged layout of the fortress Outer Heaven) while dropping key elements — including Metal Gear itself. Snake's Revenge borrows a lot of specific elements from its predecessor's NES port, such as the opening sequence that involves infiltration through the jungle. And as out-of-place as its side-scrolling segments feel, they seem an almost unavoidable result of being on NES, where 2D platformers ruled supreme. And besides, NES sequels often went in strange or outlandish directions; even the Zelda series went side-scroller for a while. What Snake's Revenge mainly lacks is a driving vision, Kojima's steady focus on what Metal Gear should be. But at the time, he had yet to come up with that vision; all things considered, Snake's Revenge isn't bad for a follow-up project to a game that had yet to establish itself as a series.

Ten years later, Metal Gear saw its second non-canonical release. Quite in contrast to Snake's Revenge, though, Ghost Babel for Game Boy Color reflected the newfound esteem in which the series suddenly found itself in the wake of Metal Gear Solid for PlayStation.

The original Metal Gear had become a minor hit on NES, hence the NES-only sequel. But after Metal Gear 2, which launched in Japan just a few months after Snake's Revenge, the series went silent for nearly a decade. When it finally returned in October 1998, its revival exploded into the public conscious. Metal Gear Solid was no minor hit; it was a video game revolution that changed both the nature of game design and the role of storytelling within the medium. It catapulted Kojima from obscurity to celebrity and made Metal Gear a premium property.

Perhaps understandably, Konami wanted to capitalize on the PlayStation hit's good name and rebranded the Game Boy Color spinoff Ghost Babel, which launched about 18 months later, as simply "Metal Gear Solid" in the U.S. (The Ghost Babel name had plot significance, but mostly it meant the game would be abbreviated to "Metal Gear: GB," predicting the glut of Nintendo DS games with subtitles that could be shortened to "DS".) The revised title was needlessly confusing, though, and probably ended up hurting the game in the long run. Many fans simply assumed Ghost Babel was a squashed-down conversion of the PlayStation game and passed on it, weary and wary of compromised portable ports.

What they missed was a fascinating and brilliantly designed distillation of the Metal Gear concept into handheld form. Like Snake's Revenge, it took a more linear approach to the adventure, going so far as to break the quest into discrete missions and even ranking the player's skills at the end of each chapter. But despite being reduced down to 8 bits, Ghost Babel played far more like Metal Gear Solid on PlayStation than like Metal Gear on NES. All of Snake's 32-bit skills — from tapping walls to distract enemies to crawling into conduits — managed to shrink down into the Game Boy Color's confines. It was a remarkable piece of engineering and design.

What most American players didn't realize is that Ghost Babel took many of its cues from Metal Gear 2, which was still six years away from an official U.S. release. Everything Snake could do in Ghost Babel had been pioneered in Metal Gear 2; in fact, Metal Gear Solid was in many ways simply a 3D adaptation of the MSX/2 sequel. Curiously, though, while Ghost Babel drew heavily on the "true" Metal Gear sequel, it largely ignored that game's existence. Instead, it sat in the same conceptual space as Snake's Revenge: An alternate-universe sequel to the first Metal Gear.

The decade that had passed since the launch of Snake's Revenge — not to mention the blockbuster success of Metal Gear Solid — made for a radically different game from the NES sequel, though. For starters, while Kojima didn't direct Ghost Babel, he still sat in as producer, overseeing director Shinta Nojiri and his team. Ghost Babel felt far more consistent with what we know as Metal Gear today than Snake's Revenge had, even if the scenario it described existed only in its own little pocket of continuity. Here, Big Boss had actually died (for real) in Outer Heaven, and the subsequent events — the Oilix crisis in Zanzibarland, and the Shadow Moses incident motivated by the desire to recover Big Boss' corpse — never happened.

So Ghost Babel begins with Snake being called back into action from his Alaskan retirement. He meets a young communications technician named Mei Ling for the first time. His mission causes Snake to cross paths with a fiery female soldier and a socially awkward engineer working unwittingly on a new Metal Gear. Snake battles enemies with bizarre names and even more freakish powers. One of his radio consultants turns out to be a traitor. At every turn, Ghost Babel echoes the beats of its PlayStation namesake... but the adventure that unfolds across the game's dozen missions is very much its own creature.

The standalone mission structure allows Ghost Babel to feature daring, sometimes experimental approaches to level design. One minute you're sneaking through a storm sewer, the next you're riding a bunch of color-coded boxes around conveyor belts. Still, the action revolves heavily around stealth — around avoiding action whenever possible — and Snake has a full bag of tricks at his disposal. When push comes to shove (that is, when you face a boss), you have a full arsenal of weapons ranging from plastique to rocket-propelled grenades at your disposal.

Despite being an apocryphal Metal Gear entry, Ghost Babel feels far more faithful to the guiding vision of the series than any other spinoff title... or even the technically canonical Portable Ops, for that matter. And while the plot can't possibly integrate into the Metal Gear saga's storyline due to all its contradictions and conflicts, it nevertheless offers a secret hook to canonicity: At the end of the optional VR bonus missions, a cryptic voice refers to the player as "Jack" — nonsense at the time, but following Metal Gear Solid 2 (which arrived the following year), it would seem to suggest that Ghost Babel ultimately amounted to virtual reality training for MGS2 protagonist Raiden. That game's script makes it clear that Raiden "relived" Snake's previous adventures through VR, and even makes a direct reference to events of Ghost Babel amidst references to a number of other VR sims.

Ultimately, both Ghost Babel and Snake's Revenge prove that Metal Gear games can be quite good even without Hideo Kojima calling the shots. Snake's Revenge definitely holds up more poorly than Ghost Babel, but it isn't a bad game... merely an uneven one, littered with experimental ideas that didn't quite work out. But Metal Gear has always thrived on experimentation, and it's not like every weird idea Kojima implemented his games always turned out to be a winner. I'd wager a fair few Metal Gear fans would rather play Snake's Revenge than big chunks of Metal Gear Solid 2 and 4. Meanwhile, Ghost Babel turned out quite well, and most likely due less to Kojima's high-level oversight than to the fact that the tone and mechanics of the franchise were much more firmly established in 2000 than they had been in 1990.

All of this isn't to say I'm necessarily looking forward to Metal Gear without Kojima (though I am eager to see what Kojima can do without being tethered to a quarter-century of story baggage); more than I'm willing to give the series a chance even without its original designer on hand. Metal Gear is a big toy box, and other people may have interesting stories to tell with it. And if not, well, it's a good excuse to replay Ghost Babel again and relive the glory days.