Virtual Spotlight: Life Force, NES's High-Quality Lo-Fi Shooter

Konami's Gradius spinoff may not have enjoyed all the elaborate effects of other NES shooters, but it remains a treat to play even now.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

When Nintendo launched the 8-bit Famicom (you know it as the NES) in Japan, the market they entered into was in a Wild West state of existence. There were no laws yet.

And back in 1983, Nintendo was a relative nobody, an arcade manufacturer with a single hit to its name — they had no clout. Third parties didn't bother to release Famicom games for a full year after the system's debut, and once they started it quickly degenerated into a free-for-all. Anyone and everyone could publish for Famicom, so as soon as the console had gained traction over there, anyone and everyone did. And what they released was... mostly not very good. You might feel jealous that Famicom had twice as many game releases as NES, but the sad secret is that the other 50% of their library consisted mostly of raw garbage bad enough to make the most cynical licensed LJN creation look like a masterpiece. Visualize the trash that unlicensed NES publishers like Color Dreams and American Video Entertainment produced; now imagine hundreds upon hundreds of games of similar quality clogging up shelves. Imagine a world where every game was Cheetahmen II.

By the time the NES debuted in America, more than two years later, Nintendo had taken careful notes about the glut of garbage that flooded the Japanese market and put into effect some harsh countermeasures to prevent something similar from happening in America. They build a special lockout chip into the American NES hardware, a code that could (theoretically) only be circumvented by approval of Nintendo itself. The 10NES security chip also allowed Nintendo to dictate what could and couldn't be released for the system; they limited each publisher to a maximum of five titles per year, and all games had to be manufactured by Nintendo.

This scheme had both benefits (American gamers had to contend with much less complete trash than their peers in Japan) and shortcomings (publishers now found their fortunes completely dictated by Nintendo's whims). It also meant that many Japanese games couldn't come to the U.S., at least not without significant revisions. Because Japanese publishers had control over their own manufacturing systems, they could not only produce as many games as they wanted, they could also make those games as complex as they wanted.

Certain publishers who had become heavily invested in the Famicom market developed their own special game chips, which enabled all kinds of special features not native to the hardware. Some of these improvements were as simple as extra sprites or colors, while at the other extreme you had something like Konami's VRC7, which included an audio coprocessor to give the NES musical capabilities similar to those of the Sega Genesis. These were all great features — and they weren't available in American games. Because Nintendo manufactured NES games in-house, all games for NES had to run on the advanced chips Nintendo developed internally. While impressive, even Nintendo's best mappers lacked the sophisticated features that appeared in third party chips.

And so, American NES fans missed out on the worst garbage ever to infest the Famicom... but we also missed out on some of the most intricate and thoughtful games of the NES as well. In the case of some of the more popular franchises, publishers figured they could bring in enough money with the U.S. release to make a downscaled conversion to Nintendo's mappers worth the extra development investment, which is why we received a slightly watered-down but nevertheless excellent version of the high-end release Castlevania III. In most other cases, though, Americans missed out on interesting games due to all those unique chips: The simple fact was, the cost and compromises involved in scaling them down simply wouldn't have been profitable. Either that, or the game in question would have been unacceptably compromised in the process.

It's impossible to say which of these reasons accounts for the fact that NES fans never had the chance to play Gradius II: Gofer's Revenge, one of the most impressive and technically refined shooters ever to appear on the system. But given the popularity of the original Gradius — it was one of those games that seemed to be in every early NES adopter's home library — and just how much Gradius II relied on Konami's custom mappers to enable its great visual effects, chances seem good that it all boiled down to technical reasons. Gradius II probably could have worked on NES, but it wouldn't have looked nearly as good or featured as many moving objects... and for a genre that hinges on looks and screen clutter, those cuts would have made for a significant and unsatisfying step down.

Still, all was not lost. Americans may have been cheated of Gradius II, but we got something arguably as good: Life Force.

In some ways, Life Force seemed more advanced than its unlocalized counterpart. It lacked some of the other game's most impressive visual effects, yes, but on the other hand it allowed for two-person simultaneous play. It also included far more variety than the core Gradius titles, switching the viewpoint on the action from side-scrolling to top-down in even-numbered stages. On top of that, Life Force also added two entirely new stages to the NES version over its arcade counterpart. It may not have been the most technically proficient NES shooter, but in terms of sheer entertainment value, it quite possibly was the best.

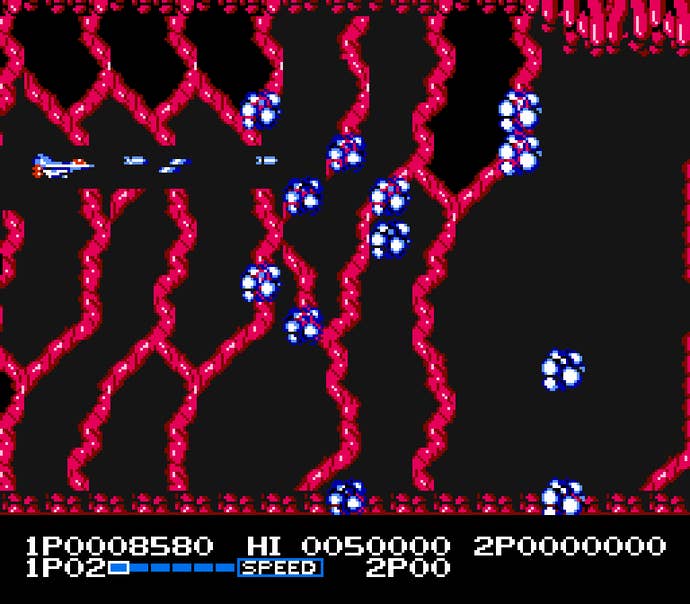

While Life Force didn't bear the name Gradius, it was essentially the same thing, plus an alternate perspective and cooperative play. The game had undertaken a long and complicated journey to home consoles; originally released under the name Salamander in Japan, the American Life Force arcade game was basically the same thing but with some revamped power-up mechanics and weird changes to the visuals that made the whole thing seem more biological than cosmic. The eventual NES release, despite bearing the name Life Force, had more in common with Salamander... plus, its power-up system underwent another massive revision in its home conversion, ultimately resembling the Gradius system quite closely. Capsules gathered from defeated enemies would cause a power-up meter at the bottom of the screen to cycle through different abilities: Speed boosts, missiles, different guns, and of course the iconic Options to double or even triple your ship's firepower.

Compared to the Gradius games, Life Force felt far more fluid and energetic. It borrowed quite a few beats from Gradius, but it always put a different spin on them. Familiar threats like volcanos and bubble-spewing Maoi heads returned, but those battles transpired through a different point of view than in the older game.

Also helpful was the fact that Life Force, while unflinchingly difficult, offered a few more niceties to the player than true Gradius games: Not only could you team up with a friend for simultaneous cooperative play (which was insanely fun despite the hellacious slowdown when two ships decked out with Options and full weapon loads tore up the screen at the same time), but building in an allowance for coop play forced Konami to change the nature of player respawning upon death. Where Gradius sent players back to a checkpoint, tragically unarmed, Life Force allowed players to maintain their current progress, zipping in from the left side of the screen. Even better, a defeated player's Options would slowly drift off the screen, opening up the possibility that you could snag them as you returned to action, greatly evening the odds for your next attempt. And if all that weren't enough, the famous Konami Code didn't power up your ship to full power in Life Force; it granted players 30 lives, as in Contra.

As a result, Life Force worked on multiple levels: It could be treated as a sort of "content tourism" by a pair of players armed with 30 lives apiece (plus several continues), making it the rare NES shoot-em-up that could be completed by an even vaguely competent player. Yet it also excelled as a legitimate challenge; play solo without the extra lives cheat and even now Life Force proves to be surprisingly tough. It's never as hard as the original Gradius, but that's not such a bad thing — Gradius could often seem unfairly stacked against the player, whereas Life Force feels more balanced.

In hindsight, Life Force is probably so good and so accessible because of the brief window of time in which it debuted. The blistering player abuse of the arcade era, where amusement vendors demanded a new coin drop every couple of minutes, didn't necessarily have a place in home gaming. Developers could afford to relax their grip on players' throats — after all, they already had their proverbial coin drop the moment a consumer took the game home. The rental industry and resale shops like Funcoland hadn't yet driven publishers to demand the creation of games that couldn't be beaten in a weekend, and as such Life Force could afford to cater to a wide range of players.

With endlessly inventive level designs ranging from a narrow corridor between two suns to an ancient Egyptian temple to the obligatory technological bio-horror of the final stage, Life Force packed tons of variety into its 10 stages. Its music, unsurprisingly, was best-in-class quality. It was equally entertaining solo or with a friend, and learning the ins and outs of the game enough to complete it on a single credit without cheat codes still makes for an entertaining test in skill.

Life Force may not have benefited from top-tier custom NES tech, but it didn't need to. Great game design and skill-driven fun always manage to stand the test of time, where cutting-edge graphical effects eventually become obsolete.

InterfaceThe Gradius power-up system works much better here than the arcade version's linear upgrades. And the decision to abandon checkpoints makes for a remarkably merciful shooter.

Lasting AppealFun to play casually and worth mastering in depth, it's a high point of 8-bit shooter design.

SoundIt's a Konami action game for NES, and that means it sounds phenomenal. A master class in chiptunes.

VisualsWhat it lacks in flash, Life Force more than makes up for with thoughtful visual design and variety.

ConclusionIt took a deft touch to create an 8-bit shooter that would remain fun to play decades later. Countless shooters of the '80s crashed and burned, as proof. But Konami nailed it with Life Force, pushing the limits of the basic NES to create a game that could be enjoyed worldwide, and for years to come. Smartly designed and just as fun with a friend, Life Force remains one of the true classics of the NES.