Thimbleweed Park Review

Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick’s new point-n’-click adventure game is about, well, point-n'-click adventure games.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

There’s a corpse pixelating underneath a bridge in Thimbleweed Park, and no one can bother to shuffle it away, not even the coroner. This is par for the course of this bizarro town: where there’s 3000 names in the phone book, but only a handful of actual residents.

At the start of Thimbleweed Park, you play as—stop me if you’ve heard this one before—two quirky federal agents. Agent Ray plays the part of the realist: she’s just there to do her job and solve this case. Agent Reyes is the other half, the one that finds charm in the podunk town between all the decrepit, boarded up shops. Agent Reyes is the Agent Cooper of this tale. Agent Ray is, uh, the Agent Scully. When the murder mystery gets going, Thimbleweed Park’s initial riff on Twin Peaks, The X-Files, and other weirdo feds-driven shows of the 1990s is evident, until it shuffles past that.

If this feels familiar, it’s probably because Maniac Mansion, the 1985 point-and-click adventure game from Thimbleweed Park’s creators Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick, followed a similar formula. The spiritual predecessor to Thimbleweed Park was at first a parody of the B-movies and horror films of its time. That was, until it evolved beyond that, inventing its own language that would come to define LucasArts as a creative force to be reckoned with, changing all computer games onward.

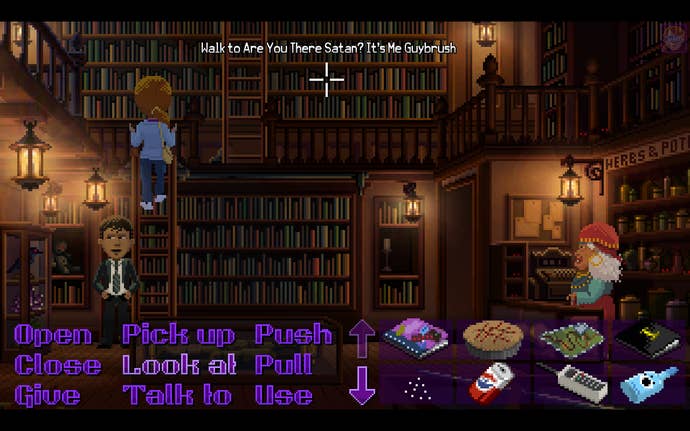

Thimbleweed Park, aware of its own leanings on nostalgia for that niche genre, narrowly sidesteps the trap door it sets for itself. What might otherwise feel as nostalgia baiting, finds itself right at home in the delightfully odd and self-referential Thimbleweed Park. Such as finding a book scrawled by 'G. Threepwood' in the library, surprisingly marking this as the second game in the past year that makes reference to the clumsy pirate of Gilbert and Winnick’s own The Secret of Monkey Island (the other was, oddly enough, Uncharted 4). Or spotting Purple Tentacle in a crowded scene, with that fleeting sight being the end of that particular call out. Thimbleweed Park wouldn’t exist if it weren't for the games Gilbert and Winnick spearheaded before it, and while paying the games that made their careers light lip service, they make it functional. This oddball town is a society that wouldn’t exist without adventure games haunting its every breath.

As Thimbleweed Park opens up beyond its Main Street strip, three additional playable characters are introduced. I already know them. Two I played in minor flashback sequences, the third was just around. In addition to Agent Reyes and Agent Ray, there’s Franklin, a lonely ghost who died of mysterious circumstances, longing only to speak to his daughter one last time. There’s Ransome the *Beeping* Clown, where beeped out swear words embellish his every utterance. He’s also an annoying *beep*, to be completely honest. Finally, there’s Delores, who ended up being my favorite character in the game.

Delores is a game developer, or at the start, an aspiring one. She goes off to work at Mmucas Flem Games (haha), before returning to her family’s home in Thimbleweed Park when tragedy strikes. Delores' return, alongside other events, ushers the real game onward. The game where you switch seamlessly between the five perspectives, checking off tasks on a list, hunting for clues and desperately trying to avoid collecting any item that may be a red herring. It's during this time that Thimbleweed Park comes into its own; beyond snickering call-backs and parodies of off-kilter 90s federal agents. Thimbleweed Park becomes its own adventure game, while playing with the legacy that plagues it.

There’s two difficulties in Thimbleweed Park: a casual mode and a hard mode. The hard mode gestures toward a "traditional" point-and-click experience, complete with even more obtuse, mind-numbing puzzles. The casual mode, I found, fared better. It leans closer toward how you remember point-and-click adventures being: a sharply-written narrative, with more acute puzzles and only a few terribly mind-numbing ones to spare. I dabbled in both, but ended up finishing my initial playthrough on casual mode, where I still often found myself at my wits end on a regular basis, but in a (mostly) non-frustrating way.

In many modern adventure games, puzzles are non-existent, or too simple to even be considered puzzles at all. Thimbleweed Park abhors that, and shapes up for giving players a challenge again; sometimes for the good, sometimes for the bad. For the bad, it was when a solution eluded me a little too much and its inevitable solution felt a bit too convoluted (even for a point-and-click adventure game). For the good, I'd feel satisfied after pacing around town and talking to locals, trying to dig up a hint to point me in the right direction. I would conjure up the solution to a roadblock naturally this way, making me feel like the smartest gal in the world. As if someone slapped me on my shoulder, said, "there you go champ, you got it!" and I would be rewarded with a silly joke or two, or even a story revelation. That feeling of success, honestly, is how I recollect my time with the Maniac Mansions and Monkey Islands of decades past. Games that inhibit me with conundrums, sure, but solvable ones, with a joke waiting for me at the end of the road.

Thimbleweed Park is surprisingly vast for being a point-and-click adventure. Playing as its five characters, I travelled across its entire map, bouncing frequently from Delores' family’s mansion, the local ritzy hotel (complete with its own nerdy, lobby-bound convention), to the town’s main strip itself (where the game begins). It also relishes in its most minute details, like the aforementioned thousands of names in the phone book, or the hundreds (literally, hundreds) of fake book titles and brief inscriptions you'll find on book shelves or libraries across the town.

With its boarded up shops, you catch glimpses of Thimbleweed Park from its long-gone heyday. An era of the past when its vacuum-tubed technology was once the way of the future, but now finds itself obsolete and out of date. Much like the road once paved by LucasArts' point-and-click adventure games, Thimbleweed Park was a town ahead of its time before being left in the dust technologically. As games have moved forward as a medium, the simpler ways of point-and-click adventures befell a similar fate, making the empty, forgotten town of Thimbleweed Park feel especially pertinent.

Despite the highs I experienced with Thimbleweed Park, the lows were sometimes deafening. The jokes that fell flat. The puzzles that stumped me for hours on end. The characters I genuinely abhorred and longed to never spend any *beeping* time with again. Thimbleweed Park is by no means a perfect adventure game, especially when it fumbles trying to recapture the magic of the classics before it. But as I played it, it felt as if the game itself were aware that it could never live up to that weighty legacy. Thimbleweed Park was never going to be the new Maniac Mansion, no matter how hard it may try. So instead, the game opts for a different approach: by subverting the adventure game genre in surprising ways as it winds downward.

When Thimbleweed Park was Kickstarted in 2014, it was pitched as, "like opening a dusty old desk drawer and finding an undiscovered LucasArts adventure game you’ve never played before." And by its end, I feel like they made good on that promise: self-referential jokes, terrible characters like Ransome and great ones like Delores, convoluted puzzles, and all. It feels like a welcome b-side to LucasArts' heyday. Like a dusty ol' floppy disk, just waiting to be played.

InterfaceClick on a verb. Click on an object. Make magic.

Lasting AppealWhile the game doesn't have multiple endings, it does have branching ones for its characters. With multiple difficulties, some players may find revisiting the eerie town to be a delight.

SoundComposer Steve Kirk's score perfectly captures the lonely, troubled atmosphere of Thimbleweed Park.

ConclusionThimbleweed Park has sharp, often hilarious writing and convoluted puzzles to spare. All in all, it's a welcome return to the point-and-click adventure, even if it ends up feeling a bit like a b-side to the classics before it.