NES Creator Masayuki Uemura on the Birth of Nintendo's First Console

The man who designed Nintendo's revolutionary console recounts the system's birth and the challenges of building an international business.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

They're coming to America

Even after launching the Famicom despite all the potential roadbumps that stood in the system's way, Uemura says Nintendo's greatest challenge had yet to come: Bringing the system to America.

"I think it is safe to say that [breaking into the U.S.] was probably the biggest challenge of the Famicom's creation," he admits. "We’d heard that even if we brought it that distributors and the parties we would need to make it a success wouldn’t be interested. So this was, I think, the problem that Mr. Yamauchi, our president, wrestled with the most: 'This isn’t selling up to expectations in Japan, but we’re hearing it’s not going to sell well in America, and what should we do?'"

Both the American and Japanese console markets posed unique challenges around the time of the Famicom's debut. The system didn't make its way into the market until July 1983, by which point the U.S. had entered the "Atari Crash" phase. Sales of new games tanked sometime in 1982, and retailers, manufacturers, and publishers alike took it on the chin. By the time Nintendo began looking westward, the American console market consisted of nothing but marked-down systems and countless games piled high in clearance bins. Retailers, stung by what turned out to be an exceedingly poor investment in video games, vowed not to make the same mistake twice.

At the same time, Nintendo's Famicom had failed to make much headway in its home market, due to a lack of consumer interest and an unexpected surge of last-minute competition. Sega launched its own competing console (the SG-1000) the same day as Famicom. Meanwhile, the MSX computer standard—based around ColecoVision-like tech similar to the Famicom's—had arrived at around the same time. And soon after, Atari finally rolled out the Japanese version of the VCS, which it rebranded the 2800 in Japan.

"Although we were hearing there were going to be problems in America, that the system wasn’t going to sell, this wasn’t something we felt that the game players over there necessarily agreed with. We knew that people had respect for quality games in America."

The feast-or-famine trend once again presented itself for Nintendo: Game & Watch sales had dried up, and Uemura says retailers worried that Donkey Kong—the central software around which Famicom had been designed—had grown long in the tooth and that the idea of playing it at home no longer offered any appeal. Difficult as the going may have been in America, Nintendo's executives saw the overseas market as their only real hope of success.

"At the time, a number of companies were trying to conquer this hurdle of making a [cartridge]-based game console, but none of them were having a dramatic success in Japan in ’83 and ’84. Although we were hearing there were going to be problems in America, that the system wasn’t going to sell—and we were given concrete reasons for that notion—this wasn’t something we felt that the game players over there necessarily agreed with. We knew that people had respect for quality games in America.

"So Mr. Yamauchi and [Nintendo of America president Minoru Arakawa] were struggling with this. While we were hearing from distributors, 'No, we don’t need your console right now, it’s not going to sell here,' that there were clear reasons that we probably shouldn’t enter the market, we also knew that we had games like Donkey Kong and the Vs. System arcade games that we had made. Those were well-regarded by American game players at the time."

Conquest through conflict

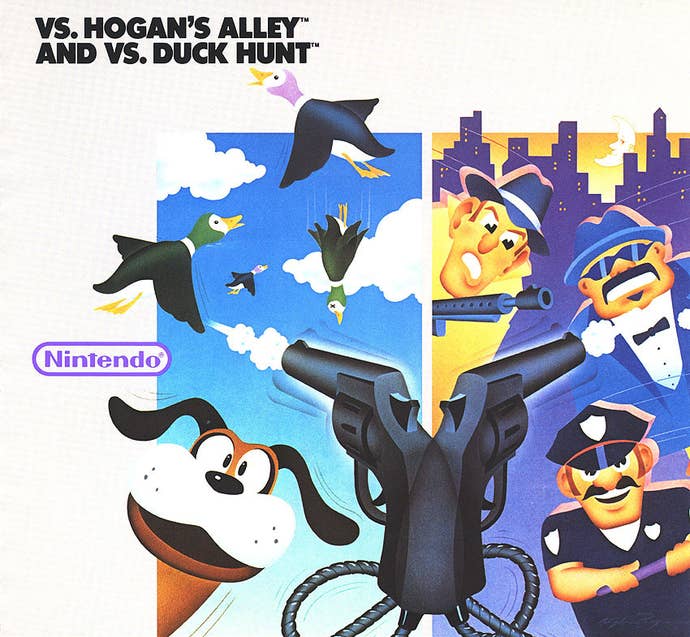

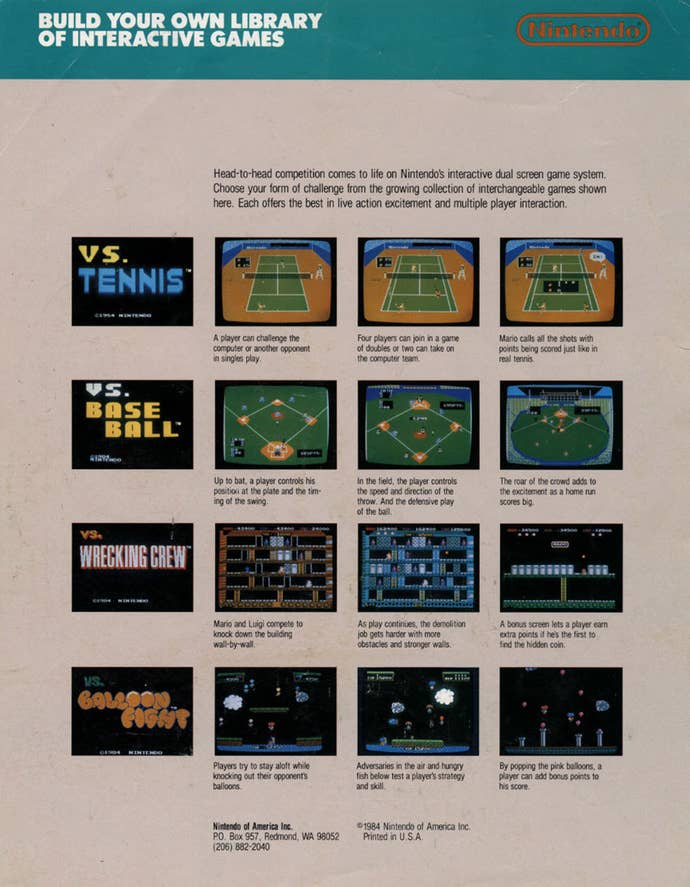

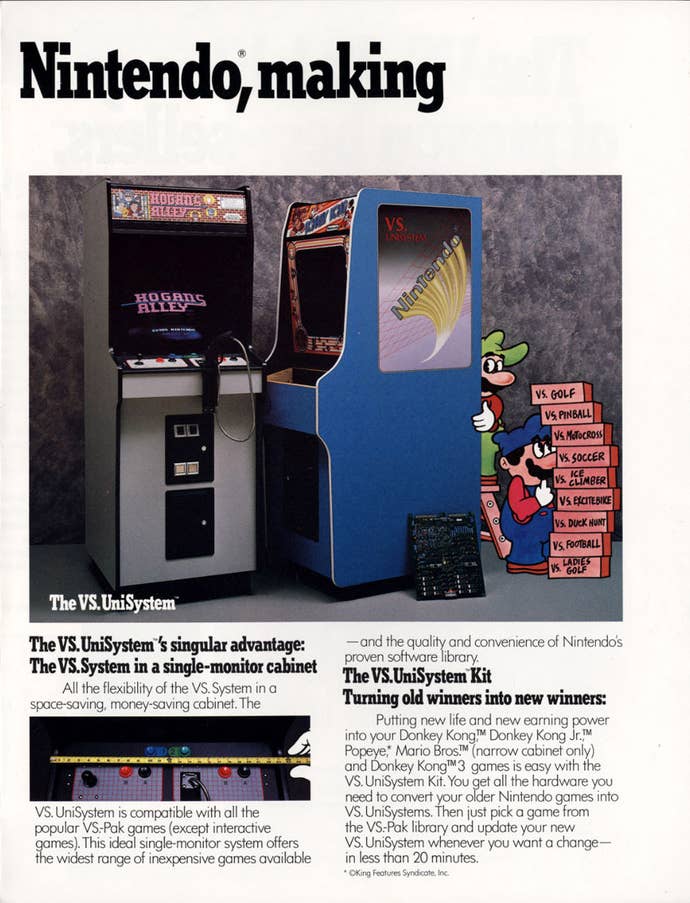

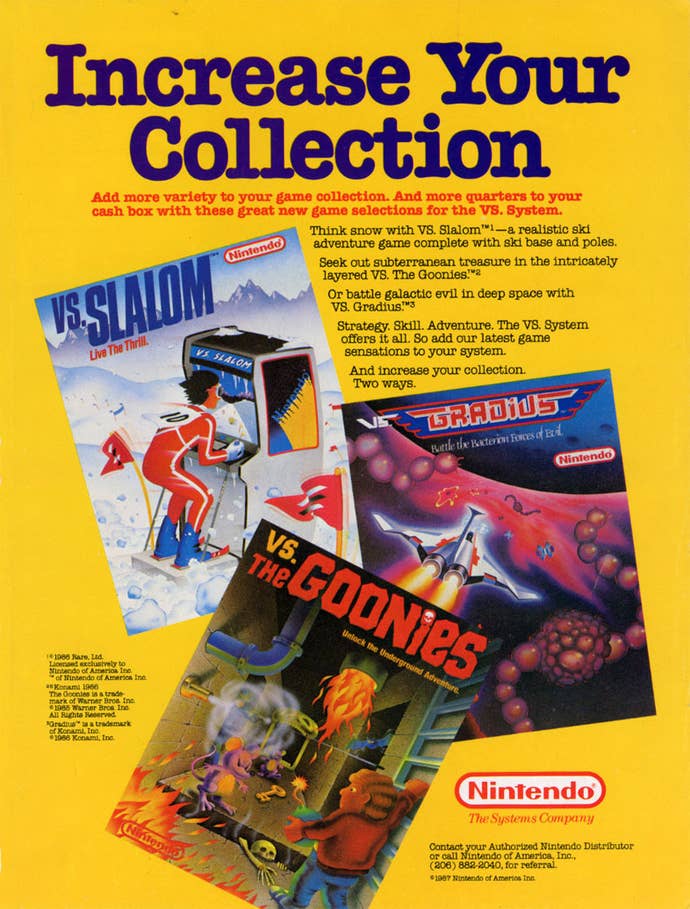

Nintendo began conducting market research in the U.S. as early as the beginning of 1984. Spearheaded by NOA's Arakawa, the central thrust of this research took the form of Nintendo's Vs. System. A brilliant idea that combined two existing assets to excellent effect, the Vs. System combined the Japanese Famicom with NOA's established arcade distribution network. In short, a Vs. Cabinet was nothing more than a modified Famicom board capable of running actual Famicom games. The games enjoyed extremely modest enhancements—Baseball, for example, featured umpire voice samples for which the less expensive cartridge didn't have storage capacity—but otherwise Vs. titles were simply the games Nintendo was selling for home users in Japan.

In 1984, Famicom hardware didn't lag terribly far behind arcade standards, so its games didn't look unreasonably primitive. And Nintendo's design appealed to arcade operators' desire to make money: The VS. System was one of the first-ever interchangeable arcade standards. Conversion kits, which allowed operators to transform one cabinet into another by inserting a new board and pasting fresh marquee and side-art decals over the old, were nothing new to the industry by this point. Nintendo's own big break had come when it converted its warehouse full of unwanted Radarscope cabinets into Donkey Kong, in fact.

However, the VS. concept took the conversion kit process to its ultimate extreme. Not only did the company sell VS. as either standalone machines or as conversions for aging Nintendo coin-ops like Popeye and Donkey Kong 3, but the VS. hardware came "future proofed," offering operators the ability to buy new games via "VS.-Pak" boards that cost far less than a new game or even a full conversion kit. After all, VS.-Paks were nothing more than arcade-ready versions of cartridges Nintendo was selling in Japan, with the Famicom hardware itself built in. SNK would see even greater success with a similar concept nearly a decade later through the Neo•Geo's dual AES/MVS format. For Nintendo, however, the VS. line wasn't the point of their business but rather a chance to keep their arcade lineup lively while getting some extra mileage out of games that hadn't found much traction with Japanese home consumers... and, of course, to do some market research.

Nintendo sold the VS. concept in all key territories at the time: Japan, Europe, and the U.S. According to Uemura, the line bombed in Japan, while in the U.S. it performed remarkably well. "Japan doesn't like competitive play in games," he says, "but America loves it." The VS. series debuted with Tennis (in March 1984, according to Nintendo's sales literature), and interchangeable boards for Baseball, Golf, Ladies' Golf, and Pinball appeared by the end of the year.

Around this same time, Nintendo attempted to gauge consumer interest in the Famicom more directly: They took the console to the 1984 Winter Consumer Electronics Show as the sleek heart of a Coleco ADAM-like modular home computer called the AVS. The AVS, or Advanced Video System, may well have been the most ’80s-looking thing Nintendo ever designed, all angular lines and low profiles. The AVS incorporated all of the Famicom's expansion capabilities (the keyboard, the Data Recorder tape cassette, and a light gun design that Star Trek: The Next Generation would rip off for its phasers a few years later); it even traded out the classic cross pad controller for a square D-pad reminiscent of the one Sega would incorporate into its Master System. Despite its cool, futuristic look, though, the AVS left prospective buyers cold. It was clearly more of the same video game hardware that no one wanted.

Yet Nintendo refused to be deterred by the AVS's chilly reception at CES. As Uemura explains, "Because we had these two conflicting opinions from distributors and from what we understood was the opinion of the player base, that kind of spurred us on and say, 'Well, we’ve got to get to the bottom of this! Let’s do it! Let’s give it a try!' And I think that philosophy is something you can say has been true about Nintendo’s history: 'If it’s difficult, we should give it a try.'"

The solution the company arrived at? Smoke and mirrors. Clearly, American consumers hadn't grown tired of video games, as the popularity of the VS. System could attest. At the same time, however, retailers wanted nothing to do with the medium, as most shops were still digging themselves out from an avalanche of unsold Atari games, bailing out a flood of red ink. The challenge would be to figure out how to convince retailers to buy in to the system; once that problem was solved, Nintendo felt confident that software-starved game enthusiasts would do the rest.

The company abandoned the AVS concept altogether; rather than attempt to sell the Famicom to Americans as the heart of a futuristic computer, they'd sell it as a whimsical toy. Handily, Nintendo had ample experience selling toys, and the new console concept—the Nintendo Entertainment System— fell directly into their wheelhouse. Gone were the keyboard and tape cassettes, along with the elegant, low-profile console case. In its place was a (somewhat) interactive robot designed very much in the style of Tomy's Omnibot 2000, a more traditional look for the light gun, and a radically redesigned console.

The NES itself went from being a slim slice of the future to a boxy chunk of plastic that bore a striking resemblance to a VCR. That was by design, Uemura says: The Atari 2600's top-loading style had more or less destroyed the image of console game systems. Nintendo redesigned the NES to be a front-loading system, with cartridges inserted horizontally and pressed down into the machine by means of an elaborate spring-loaded carriage rather than plugged directly into the cartridge slot. Likewise, the Famicom's tiny cartridges were doubled in size—not because NES carts contained more memory or tech inside, but in order to make the front-loading console easier to use. NES boxes even came with styrofoam spacers inside to bring the packaging up to the size of VHS tape cases, so they'd look right at home together on a home entertainment center shelf.

Uemura laughingly admits that no one actually understood how to use R.O.B., the Robot Operating Buddy, but the little guy did his job: He created a sense of novelty the convinced a few toy retailers to buy into the NES. From there, hands-on demos and word-of-mouth did the trick. From a limited 1985 test launch in New York City, the system spread like wildfire across the U.S. in short order; by Christmas 1987, it was the hot toy, the one everyone wanted and that was sold out everywhere.

"That philosophy is something you can say has been true about Nintendo’s history: 'If it’s difficult, we should give it a try.'"

Though Nintendo made considerable changes to the Famicom in order to transform it into the NES, most of them were cosmetic in nature. Aside from the addition of the 10NES security chip and the removal or rearrangement of a handful of features—the loss of an expansion port, the addition of sockets to do away with hardwired controllers—Nintendo's revisions didn't change the system's fundamental technology in any meaningful way. According to Uemura, simply making the Famicom salable in the U.S. proved enough of a challenge.

"From a time perspective," he says, "although there’s two years separating the launch of the two, we were actually quite busy in preparing for it. We didn’t have a lot of time to observe [possible improvements] and then make use of them in moving toward the NES. This was at a time we had been told by people such as Mr. Arakawa and our folks at NOA that video games wouldn’t sell in America, and so we were going in blind, including those preparations to use things we’d learned from the Famicom, and we’re taking a risk in that way.

"So we kind of made the decision, 'Well, we don’t really have the time to make any large changes to the hardware, so let’s use the hardware as much as we can as-is and focus on overcoming this obstacle of the idea of games not selling or games not being popular in America, and put our efforts into getting past that.' That meant bringing the games over as well, and many games had come out in Japan at this point that had these more fun bugs that I mentioned, and we intended for games like that to be able to come out in America as well and just kind of accept that as the nature of the beast and move forward."

It's good to play together

Perhaps not surprisingly for someone who played such a unique and pivotal role in video game history, Uemura doesn't really fit the stereotypical image of an engineer. Far from being shy and uncomfortable with public speaking, he's an engaging storyteller, whether contemplating long-ago business strategies or chuckling about the fact that he can stomp his grandkids when they play together on the old dedicated consoles he made for Nintendo in the ’70s. He made the jump from engineering to academics more than a decade ago, and his areas of personal interest these days fittingly have less to do with electronics and more to do with humanities and socialization: The nature of play around the world.

"It is surprising to me [that the NES is so well-loved all these years later]," he says. "Working at Nintendo, which is essentially where we’re making the tools of play, you grow accustomed to the short life cycles that products and trends have, so I am surprised that something I was involved in has ended up having such a long-lasting influence and interest among people.

"You know, games themselves are kind of an example of these short life cycles, and we see that even today, but the medium of video games is something that has proven to have the staying power, and has lasted and continues to thrive. I’ve gone into academics in recent years, and one of the things I’ve studied is the history of play around the world, and I’ve seen that same trend in my studies. One thing I’ve found is occasionally you do find a type of play, a medium of play, that sticks around a long time, that overcomes the more common concept of a short-lived trend.

"So, in one sense, the fact that the Famicom and NES have been around now for 30 years is a really long time, as I mentioned, but in another sense, looking at some of these modes of play that are around the world and are still around after thousands of years, it’s quite a short time."

"So now, and I don’t know the answer to this yet, but there’s the question: Will video games as a medium be a mode of play that have that truly long-lasting staying power? We have yet to see the answer to that."

Cover Story: 30 Years of NES

NES Creator Masayuki Uemura on the Birth of Nintendo's First Console: An oral history of the NES's invention, from its inventor

Retronauts Looks Back 30 Years to the NES Launch: A star-studded podcast

30 Years of NES, 30 Interesting NES Facts: Bite-sized NES trivia