A Brief History of Video Game Violence, Part 1: Death Race to Mortal Kombat

Check out the most notable moments that turned heads and stomachs throughout the history of video games.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Every new medium goes through the same process: Decades of hand-wringing over the possible corruption of society, followed by gradual—if reluctant—acceptance. And really, no format is safe from this initial hysteria. Even the reading of fiction caused its share of tongue-clucking—really, you're just going to stare at some lies a stranger printed on paper? Whatever, dude; I'll be over here with my Bible.

That's not to say all concerns are unfounded, but the legitimate ones usually get drowned out by the most ignorant (and typically loudest) outcries. And, at times, this sentiment feels doubly true with video games. You'd think if pinball didn't turn a generation into irredeemable degenerates, nothing would, but our medium has seen its share of outrage-based controversies throughout the past four decades. Let's explore them together as we try to suppress the malevolent rage instilled in us from years of being trained in the deadly art of murder. Or has that study already been discredited?

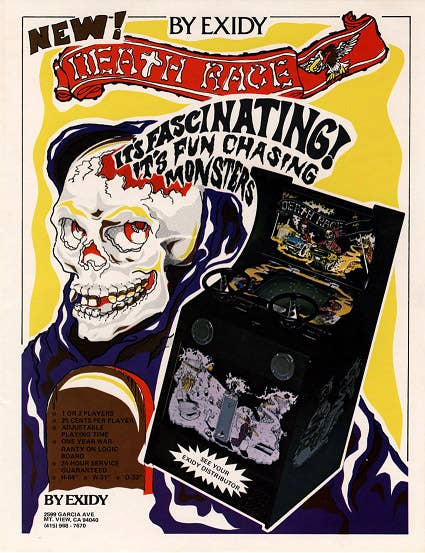

1976: Death Race - The First "Murder Simulator"

Exidy's violent arcade racer took some (possibly) copyright-infringing cues from the Roger Corman schlock-fest Death Race 2000—back when "2000" indicated the future, you see. The game, which originally began life under the unfortunate title "Pedestrian," tasks players with using their crudely rendered car to run over similarly crude depictions of humanoids known as "gremlins." And while most kids probably played a nearly identical game with army men and RC cars in their own living rooms, Death Race's depiction of vehicular homicide proved too intense for some. (But keep in mind the game's strictly black-and-white graphics weren't really capable of displaying blood and viscera.)

From the beginning, Exidy seemed intent of ruffling feathers. Gotcha!, one of their previous arcade releases, was known as "the boob game" thanks to its two suspiciously shaped controllers—hell, the flyer alone makes it look like a sexual harassment simulator in the groovy '70s. And years later, Exidy's Chiller would push the envelope even further with its outrageous gore; what other game has you blowing chunks out of torture victims in its very first level? It's hard to blame the developer for their cynicism, though, seeing as controversy so often helps fuel sales. "We're not at all ashamed to talk about 'Death Race,'" says former Exidy vice president Paul Jacobs. "The net result was that we handled the whole thing very well and the publicity was good for the industry... As for the game, the media attention made it more popular than we ever imagined it would be... We built over ten times the number of machines in the original release."

A sequel, Super Death Chase, was put into production thanks to Death Race's sudden popularity, though this focus on violence never sat right with Atari co-founder Nolan Bushnell, who viewed Exidy's creation as a black mark on video games. "We were really unhappy with [Death Race]," says Bushnell. "[Atari] had an internal rule that we wouldn't allow violence against people. You could blow up a tank or you could blow up a flying saucer, but you couldn't blow up people. We felt that that was not good form, and we adhered to that all during my tenure."

[Editor's note: If you'd like more info on the Death Race controversy, check out this extremely thorough article on Game Studies, where you'll find the sources for the quotes above.]

1980s - The Great Cleansing

By the '80s, moral panic shifted away from video games to other burgeoning forms of entertainment. Rap music threatened the status quote with its blunt, often socially conscious lyrics, while Dungeons & Dragons threatened to steal our children's very souls via the pact with Satan printed on every character sheet. And outrage was no longer generated over what games kids were playing, but rather, where these games were being played. In these days, the ever-popular arcade was often viewed as a smoky den of ill repute, where innocent children could be led down various life-destroying paths: drugs, gangs, petty theft, and so on. These more serious issues definitely outweighed any digital violence a child could witness within the arcade's dank interiors.

Just a few short years after Death Race, arcade cabinets wormed their way into our malls, convenience stores, restaurants, and bars, making this form of entertainment absolutely ubiquitous. And the state of gaming at home struck a colorful, cutesy tone thanks to the efforts of Nintendo. Their censorship policies made it so anything that could possibly offend would be wiped from the localized version of their console's games—which explains why they decided to leave something like Devil World in Japan. (Also, it's not very good.)

Video games on home computers, though, were growing more violent and sexual, but the hobbyist nature of these extremely expensive machines meant that if your kid saw something he or she wasn't supposed to see, it was probably your fault. And while Nintendo managed to avoid controversy outside of the strange addiction it had instilled in America's kids, developers bristled at the often arbitrary nature of their censorship policies. If you'd like a front-row seat to this kind of frustration, this article details the difficulties involved in bringing the slighty edgy Maniac Mansion to the NES.

1993 - Here Comes the ESRB

By the early '90s, controversy would be generated by a very unlikely game: Night Trap, which originally entered production in 1987 for the unreleased, VHS-based NEMO system. In retrospect, Night Trap's fairly lighthearted sendup of the slasher genre—featuring a musical interlude where tennis rackets and hairbrushes act as makeshift guitars and microphones—wouldn't merit more than a PG rating, but its use of a fairly new technology managed to generate some major anxiety. These weren't the simple stick figures of Death Race getting run down in the streets; Night Trap features real actors in fictional peril thanks to the full-motion video capabilities of the Sega CD.

Both Night Trap and Mortal Kombat (which also used real actors, albeit in digitized sprite form) served as the two major punching bags during the 1993 Senate Committee Hearings on Violence In Video Games, where our elected leaders largely missed the point. Despite Sega's institution of their own ratings system, they bore most of the blame for third-party titles published on the Sega Genesis. Bill White, representing Sega, tried to insist certain titles for his company's hardware were intended for adults, but Nintendo's Howard Lincoln—who got the company out of hot water several times in the past—fired back with a perfectly calculated "think of the children" response:

"I can't sit here and allow you to be told that somehow the video game business has been transformed today from children to adults. It hasn't been, and Mr. White, who is a former Nintendo employee, knows the demographics as well as I do. Furthermore, I can't let you sit here and buy this nonsense that this Sega Night Trap game was somehow, only meant for adults. The fact of the matter is, this is a copy of the packaging, there was no rating on this game at all when the game was introduced."

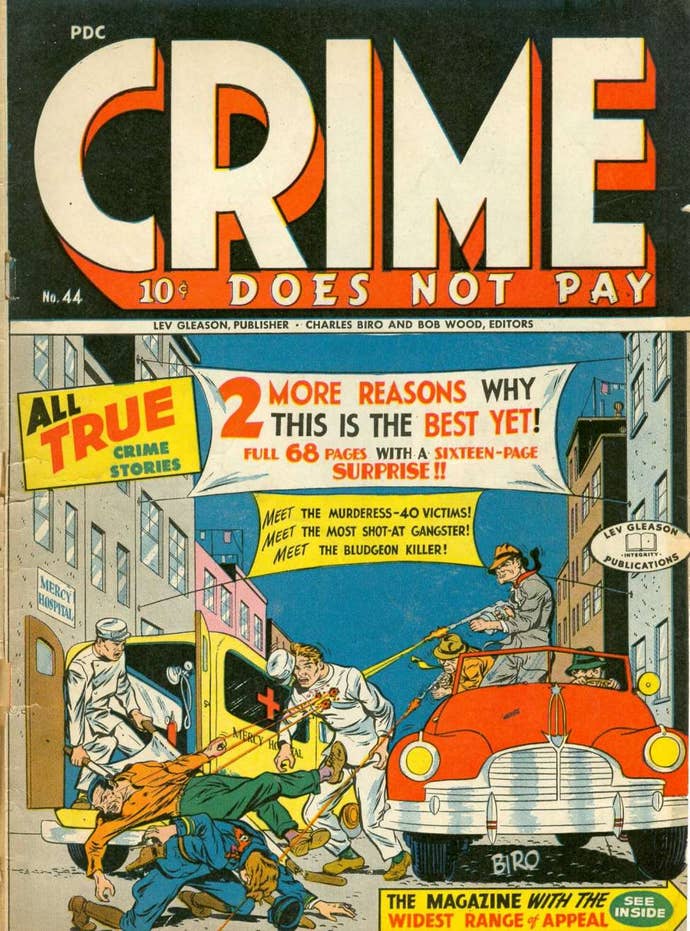

This one-day dust-up on the Senate floor let to the 1994 institution of the Entertainment Software Ratings Board (or ESRB), a self-regulating entity that would allow the video game industry to continue without government intervention. Compared to other forms of industry-wide self-censorship, video games mostly escaped unscathed. The now-defunct Comics Code, for instance, killed off romance, crime, and horror comics completely (leading to the creation of MAD Magazine), and the Hays Code forced filmmakers to work under laughably patronizing regulations until the '60s "New Hollywood" movement (which gave us filmmakers like Speilberg, Scorsese, and Coppola) brought an end to its puritanical edicts.

Even so, much like the MPAA, the ESRB stands as an imperfect system, judging games based on values not necessarily shared by the entirety of consumers. It's better than the alternative—government regulation—but some subject matter (mostly sexual content) remains taboo. Thankfully, Rockstar and other provocateurs have been pushing the limits of the M for Mature in recent years with content (like *gasp* visible human penises) that would have landed them in the Adults Only rating No Man's Land just a generation ago.

We've only reached the mid-90s, and this history of video game violence still has a ways to go. Keep your eyes on USgamer for Part 2, where we'll examine the last twenty years. See you then!