Consoles You've Never Heard of: Amstrad GX4000

On the 25th anniversary of its disastrous European launch, Jaz takes a look back at the ill-fated British console, the Amstrad GX4000.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

A quarter century ago over in Europe, consoles were beginning to take off in a big way. That might sound odd to Americans, who'd had a booming console market dominated by Nintendo since the mid-80's, but over the pond, the gaming business was a completely different beast.

There, the ZX Spectrum, Commodore 64, and, to a certain extent, the Amstrad CPC home micro computers had ruled the roost during the same time period. But as gamers looked to upgrade their systems to something new and more powerful, they began to turn to consoles as an option.

There were other, newer home micro choices in the form of the Commodore Amiga, and the Atari ST, but they were quite expensive to buy, and while both machines were moderately successful, they didn't quite fly off the shelves in the same way that the prior generation of home computers had done. With consoles like the Nintendo Entertainment System, upcoming Super NES, and Sega's Mega Drive (aka the Genesis) creating a huge buzz in the gaming press, and the option to import a hot new console from Japan such as the PC Engine providing a more cost-effective route into new-generation gaming than buying an expensive computer, consoles began to garner a fast-growing share of the gaming market.

Amstrad was a big home micro producer at the time, and owned the rights to the ZX Spectrum line of computers. However, it was faced with a dilemma. The company didn't have a 16-bit home micro to compete with the likes of the Amiga and Atari ST, and with sales of its 8-bit computers swiftly dwindling, Amstrad decided to make a rash move and jump into the console market.

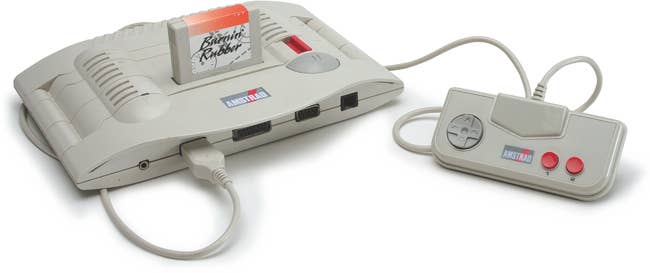

However, the solution to its problems was not ideal. The GX4000 console certainly looked the part – it had controllers that looked almost identical to the ones on the NES, and the machine itself seemed very crisp and neat thanks to its stylish white and grey box. However, what was most important was its internals, and there the machine was distinctly lacking.

What Amstrad did was create a system based on its CPC line of 8-bit computers so that it would be compatible with software produced for that machine. A laudable concept in principle, since users would essentially have access to hundreds of video games produced for those computers… except that all CPC software came on cassette, and there was no cassette drive or port on the GX4000. Instead, the idea was that software developers would convert their cassette games and put them onto cartridge in typical console style. That sounds like a good idea, except that those games cost around ten to fifteen dollars on cassette, and would cost upwards of forty bucks on cartridge - for basically the same game.

The other major strike against the machine was that CPC technology was seriously outdated at this point. Based on an 8-bit Zilog Z80 4 Mhz chip, the GX4000 was capable of producing a 160x200 pixel, 16-color display in mode 0, and a 320x200, four-color display in mode 1. In other words, it really wasn't very good compared to the then cutting-edge Mega Drive, which also had an 8-bit Zilog Z80 chip – but that was used to control sound and provide backwards-compatibility for Sega Master System games. Its main chip was a 16/32-bit Motorola 68000 CPU that ran at 7.6 MHz, and it was capable of displaying 80 colors in 320x240. The GX4000 just couldn't compete with that.

Undaunted by this, Amstrad launched the system anyway, producing an initial run of 15,000 machines that hit retail in Britain, France, Spain and Italy at the beginning of September 1990, with a price tag of around $150. The system had one pack-in game, and while many games were announced by software companies thinking that if the machine did take off, they'd make some easy money converting their old cassette games to cartridge, only a couple of games accompanied the machine at launch.

The problem was that companies had made a big proviso in their agreement to make games - the GX4000 needed to be a success for them to convert their games to cartridge, but that created a classic chicken and egg situation. The machine wasn't going to be a success if there were no games available for it, and nobody was going to make any games for it unless it was a success. Worse still, Gamers quickly realized that if they really wanted to play Amstrad CPC games, they could pick up a second hand computer for very little money, and buy all the best games available for it for next to nothing, since at that time many Amstrad users were selling their game collections to fund either a shiny new Japanese console, or an Amiga or Atari ST.

Because of that, the system simply didn't sell. During the Christmas period in 1990, when Amstrad expected to produce a second run of systems to keep up with demand, the machine languished at retail. Price cuts quickly followed in the New Year, but even that didn't help shift units. Retailers began to panic, and sold the machine for as little as $30, but with companies canceling their plans to make GX4000 games left, right and center, they could barely give the machines away.

In the end, just 27 games were produced for the GX4000, many of which were produced in their hundreds, rather than thousands, and a second run of systems never happened. These days, the system is largely forgotten in Europe – although it has become a bit of a rarity that is prized by hardcore system collectors – and it's pretty much completely unknown in the US. But I thought it was worth telling its cautionary tale on its 25th anniversary as proof that it's never a good idea to try to swindle gamers with old, out-dated technology in a new box.

.jpg?width=291&height=164&fit=crop&quality=80&format=jpg&auto=webp)