How PlayStation’s The Getaway managed to outdo, yet fail against, GTA 3

The ambitious PS2 action game is still revealing secrets to this day.

“In many ways GTA 3 was inferior to what we had created,” Mike Rouse says, “and this was emboldening.”

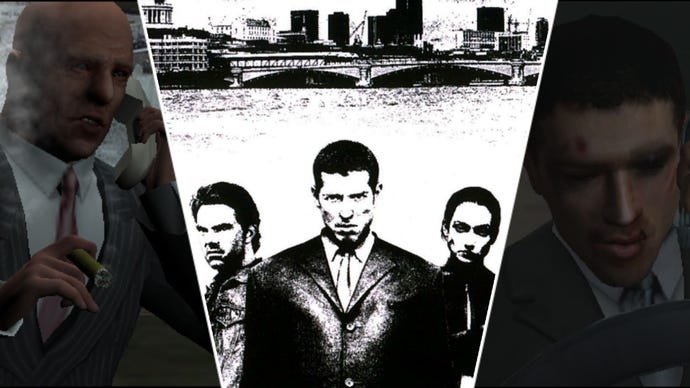

That might sound like hubris or denial coming from a developer on The Getaway. As GTA 5 celebrates its third major launch across a third console generation, it’s safe to say that the pre-release competition between Sony’s Team Soho and Rockstar North is now long-settled in the latter’s favour. There are no Oasis vs Blur-style discussions still raging about who won this particular battle for pop cultural dominance.

Yet Rouse is right, in some respects. While The Getaway’s linear adventure through London was out of step with GTA’s new free-roaming paradigm, the passage of time has shown it to be a forward-thinking game – putting actors' faces and performances in-game, and rejecting arcade-like elements in favour of imbuing its city with detail and authenticity. In fact, Rockstar’s eventual decision to fund and publish LA Noire – a follow-up to The Getaway, built by some of its core team – was tacit acknowledgement that its rivals at Team Soho had been onto something all those years ago.

Back then, Rouse had joined Sony as an intern, first working on This is Football 2002 – a convenient way of carbon-dating his career. Within months, he’d finished university and joined Team Soho full-time to contribute to The Getaway. “This was an extremely exciting time for me,” he says. “To get to work for PlayStation making a AAA game as my first title was beyond what I thought I would achieve.”

If everything about The Getaway’s development was new to Rouse, the same was true for the rest of the team, no matter their level of experience. “This was one of the first games of its kind,” he says. “Every day felt like you were doing something that had not been done before. There were extremely few points of reference.”

Motion capture, then an art new to the entertainment industry rather than the backbone of AAA gaming as it is today, was heavily exploited to deliver the playable version of Snatch that The Getaway promised. “It was amazing to see the actors interacting with wooden props,” Rouse says. “And then seeing in real-time the characters on screen mimicking the actors. To see it in a game was still relatively rare.” When blackmailed mobster Mark Hammond visibly wrapped his fingers around a chunky mobile phone – the only lifeline to his kidnapped child – the tension was palpable.

It’s a choice that reflected Team Soho’s determination to channel its budget into meticulous, granular detail – despite enormous scope that took in 10 square miles of London. Rouse and a colleague would travel across the UK with a list of cars to photograph; although The Getaway featured many licensed vehicles, the team couldn’t rely on reference materials sent by manufacturers.

“Everything we created had to be real or as close to real as possible,” he says. “Everything from the tires deflating, to windows smashing, to real-time deformations in the bodywork. The cars were leagues ahead of what you could find in any other game at that time, and it was great fun creating them.” As the studio built a condensed-yet-faithful mirror image of the capital’s streets, Rouse’s two hour daily commute into Soho became surreal, his virtual world and reality converging.

Up in the Scottish capital, Rockstar North was acutely aware of Team Soho’s open world aspirations, and vice versa. “We were actively competing with them to come out first,” Rouse says. “Both teams were aware of each other’s projects.”

Ultimately, The Getaway’s complexity meant a year-long delay, and so GTA III got there first. It quickly redefined public expectations of what an open world was and how it should function, hurting The Getaway on release. “As I look back, I think we created something very different,” Rouse says. “Open world was the big new thing at that time and gamers could not see past this. In many ways, I think The Getaway is closer to a game like Uncharted than it is GTA.”

In the years since, some have managed to reevaluate The Getaway on its own terms – like Nik, a 26 year old translator who goes by RacingFreak on YouTube. Nik runs thegetaway.uk, a portal intended to replace the defunct official sites for the Getaway games, as well as provide a home for its community and preservation efforts.

The Getaway was the very first PS2 game Nik ever played, and won him over with its flawlessly animated cutscenes and mostly naked HUD. He even enjoyed the challenge of navigating London using subtle turn signals, rather than a directional arrow. “What really impressed me right away as a car enthusiast was seeing all these licensed vehicles in such an accurate and detailed open-world rendition of London,” he says. “It was truly mind-blowing and quite frankly still is.” A love for British heist films and dependable telly police procedural The Bill sealed a relationship with The Getaway that has become lifelong. By the early 2010s, with the series dead and bundled into a trunk in Sony’s car park, Nik was compelled to dig into the game to discover its secrets.

“The myths about how the cut BMWs and Jaguars are lost forever were still being talked about,” he says. “It wasn’t long until my first breakthrough came with the discovery of the cut beta cars. Since then, I’ve been on a pretty much one-man mission to continue, to my best ability, documenting and researching almost every aspect of the game – at times switching to The Getaway: Black Monday, helped by the fact that both run on the same engine.”

Black Monday was Team Soho’s follow-up. Launched in 2004, it stuck stubbornly to London rather than explore new cities, and was decidedly less acclaimed. “It was a more dynamic story, there was more content, more city, and more unique gameplay mechanics,” Rouse says. “But by this time there were quite a few open-world games, and the focus was more on an arcade experience in these games, whereas The Getaway series still leaned heavily into its narrative-based gaming and its cover shooter mechanic.”

A couple of further sequels entered production at Sony, but were cancelled at different stages of development. Perhaps the true successor was LA Noire – “obviously influenced by the teams’ experiences on The Getaway,” in Rouse’s view – which even briefly featured a cameo from Don Kembry, the former Mark Hammond, playing an elder relative of his Getaway character. There’s an argument to be made, in this era of canon and crossover, that the two games exist in the same universe.

In recent years, Nik has continued his work in mining The Getaway for hidden marvels – establishing relationships with the game’s developers that made this article possible, and posting his discoveries online. A personal highlight has been successfully spawning a beta Ford Capri into the game, after years of failed attempts. Not long ago, Nik figured out The Getaway’s texture format, unlocking the potential for advanced mods like custom cars and characters.

Rouse, meanwhile, still thinks of The Getaway when he’s in London. “To this day I can make my way around based on just playing and creating the world,” he says. “I’ll find myself in a street and I recognise it and know where I am without having ever been there before.”