Behind the Art of Day of the Tentacle

COVER STORY: LucasArts alumni Peter Chan and Larry Ahern chat about the challenges of making a "cartoon adventure" under the constraints of early '90s technology.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

Capturing Cartooniness

With their new roles on Maniac Mansion's sequel, both Chan and Ahern had an amazing degree of freedom in determining the visual style for Day of the Tentacle. With the basic concept for the game in front of them, the two found inspiration in the same source—an animation legend.

Larry Ahern: Another frustration I had experienced working on Monkey Island 2 was this feeling that the different artists that were working on things were not doing one consistent style. It's like each individual artist would kind of do what they thought their version of a Monkey Island character should look like, and there was nobody officially art directing it and coming in and saying, “No, that character's off-model, or that needs to look more like this.” So, I felt like there were a lot of frustrating stylistic changes depending on the scene you were in.

And, so, I had talked about, okay, if I'm going to work as an animator on Day of the Tentacle, I really want to be able to have the authority to pull everything together and make it consistent. We should come up with character designs, and those are locked down. This is a process. We figure out what these characters are in advance, and then make sure it all matches stylistically and then everybody animates those characters, as opposed to bringing someone in later and saying, “Oh, design the character you're going to animate,” and hope it matches.

Peter Chan: [My son] was born, and, I remember watching cartoons with him. It was Saturday morning stuff, and it was Chuck Jones, Duck Dodgers, and What's Opera, Doc?. And I remember looking at it, and going, "There's something there," and then I had to do some research. And back in those days you couldn't just Google something. You couldn't go to Google and find all these images. There wasn't any, except for a few books that were out there, so, back in those days, you had to go out and buy books and then reference, get the reference from it.

LA: I was really pushing for [one consistent art style], and then, I think, out of frustration from working on Monkey Island, the characters were so small, especially their faces, it was really hard to do much of anything in terms of facial expressions on those characters. So I was wanting to push the look of Day of the Tentacle in a more cartoony direction with large heads and big googly eyes so you can see the whites of their eyes, because they're so much more expressive that way. And, I guess the original Maniac Mansion did have larger heads on the characters too, so, it was probably a little bit leaning in that direction, also. At that time, there was a limit to the amount of pixels you could move around on the screen for a character. So, we were given basically the maximum pixel height of a character, or maybe it was a pixel volume kind of thing, not that you could have it that high and super wide and fill the screen.

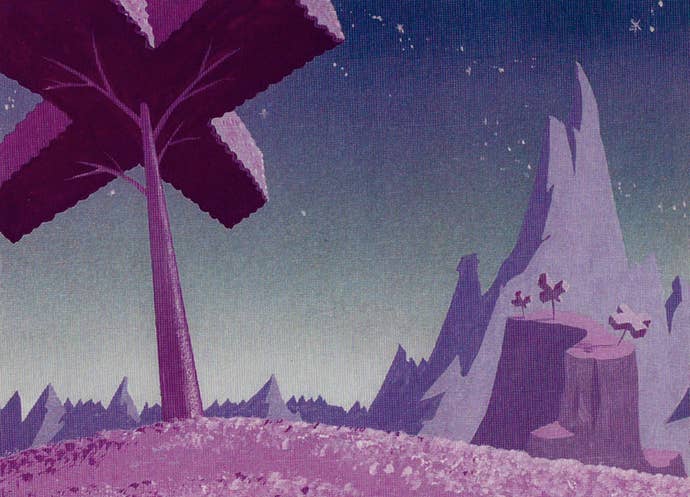

PC: I wasn't trying to flat-out do a classic [Warner Bros. background artist] Maurice Noble layout, or art style. It was inspired by him, but it was basically what Larry and I kind of chose and put together. I was looking up at Larry, too, I was impressed by all these amazing people at LucasArts. So, I looked at Larry and he was on his way to designing these characters, and I thought, "Oh my God, I've got to create environments for his awesome characters to live in." And so, I had to find that happy balance of, for everything to come together.

LA: So, that was part of the challenge: Figuring out how do you get the expressive character that you want within those limitations. So, I kind of worked on character designs based on that. What could I do, giving them larger heads, bigger eyes, and expressive faces, and still have it look like one consistent style. So, that was kind of the process, and early on it was just Peter and I working on the visual look for things. We did a lot of tests where we did some background mock-ups. We'd put some characters in it, we'd figure out how the backgrounds needed to be done so they didn't get too busy and compete with the characters, because a lot of time a character walking around a real complex background can get totally lost, and some of that's the background and some of that's the character.

PC: I wasn't trying to rip off, of course, a Chuck Jones or Maurice Noble art style. I was just trying to find a way to problem solve, basically. Then, fortunately, through that process, we were able to share the game with Chuck Jones down the road, and he was very kind, yeah. He had a lot of nice things to say about the game.

Day of the Tentacle co-director, Tim Schafer: We met Chuck Jones, we brought him in to look at the game, and we were hoping he would say something we could use as a blurb on the front of the box, but he never did. He was like, “Nice, cool.” His actual advice was, “Have you thought about making the characters not human, because, you can get away with a lot more craziness if they're not human.” When their faces are human, you expect them to look good, or to emote in a human way, but if they're rabbits you can change it all up.

Day of the Tentacle composer, Peter McConnell: About that time, Chuck Jones visited to give us a lecture. And he saw Peter's stuff, and he said, “You got to come work for me.” But I guess Peter liked the independence a little bit better, so he stuck with us, fortunately for us. So, yeah, it was, which gives you a sense of how excited we all were about what we were doing. We knew that it wasn't, while it might not have been the best, it wasn't the big screen, but it was where it was happening. It was an exciting new frontier to be working on.