A Voice for Ivalice: The Localization and Voice Acting of Final Fantasy XII

Now almost ten years removed, the localization team and voice actors look back on a magnificent work of game translation.

This article first appeared on USgamer, a partner publication of VG247. Some content, such as this article, has been migrated to VG247 for posterity after USgamer's closure - but it has not been edited or further vetted by the VG247 team.

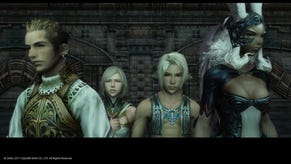

For all of the reasons that you can think of and more, Final Fantasy XII is famous. Famous for its breaking of even the most sacred of the franchise's gameplay tenants. Famous for its long and, depending on what you believe, tumultuous development cycle.

Famous for being one of, if not the most divisive games in a series chock full of them. As an artifact of a very different period in game design – especially the genre it falls into and the country where it was born — it is as radical as it infuriating, as densely opaque as it is guided and straightforward.

To those in the know, their natural response to a pretentious opening paragraph like that runs along the lines of, "Well, it is a Yasumi Matsuno joint." But that's only partly true, and simply a starting point. It's no secret that the Matsuno , the original director of the game (himself of Final Fantasy Tactics, Vagrant Story, and Crimson Shroud fame), had left partway through its development with new designers assuming and restructure the work, but the density of Final Fantasy XII mentioned above was in Matsuno's carefully built and preposterously deep world of Ivalice.

This particular game in the titanic RPG series, after all, was the only one to take place in a world already fully formed from previously made work, and with that came the rich history of a universe that already had an air of antiquity about it. Even outside of the main scenario's plot –lengthy though it was as a numbered Final Fantasy—the amount of NPCs, flavor text, and background content was a huge undertaking to be formed into life. Then, it had to be translated into English.

It's here that some of the greatest achievements of Final Fantasy XII take shape. Regardless of how one feels about the stripping and rebuilding of how a game in the series plays with its almost total MMO-like openness and intricate programmable combat, the translation and voice acting are a high point for not only the series, but a significant turn for video games both then and now. Then- free of the growing pains of a voice acted mainline entry post-Final Fantasy X, XII's diverse dialects of English, mythology-infused background text, and Easter egg-heavy references are a profound work of game translation, even for a team famous for it.

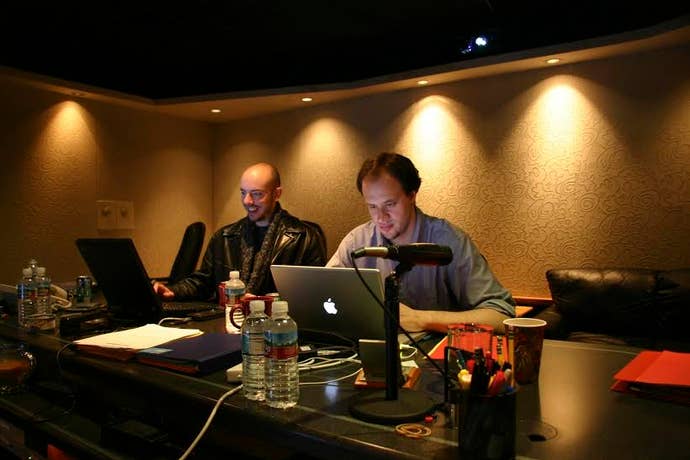

What follows is a series of interviews with the architects of that localization process compiled together into one larger mosaic. Now nearly ten years after its Western release, translators Joseph Reeder and Alexander O. Smith (whom also served as a producer for the voice work), voice/ casting director Jack Fletcher, and actors Gideon Emery and Elijah Alexander have agreed to share their varied experiences with the project and offer insights into adapting something so large as a mainline Final Fantasy game to be played by a Western audience.

Note: The interviews have been slightly edited to remove redundant questions and answers when necessary. Some answers were compiled together for ease of reading. In addition, Alex O. Smith and Joe Reeder collaborated on their responses via email, hence the decision to quote them together.

Involvement, Writing, and the Translation Process

How did you become involved, how far into development was the game when you started working on it, and how long did it take you to complete it?

Alexander O. Smith/Joe Reeder: It was about halfway complete when we started in earnest. About two years, all told [to complete].

Jack Fletcher: I was involved with the sound for The Spirits Within, which got me on to FFX, which is where I met Alex. Our connection was very important to how FFXII turned out. And of course, FFXII is when I first met Joe.

How big was the script compared to other games that you've worked on?

AOS/JR: The voice script was slightly smaller than FF10's, but the non-voiced was as large as any FF, if not larger. While we had a generous amount of time to work on the voice script (about 9 months, including the recording), which represented about 9% of the total volume of text in the game, getting through the remaining 91% of the text was a real challenge, especially for just two people. We probably made it harder for ourselves by doing things like the Victorian-era characterization on the bestiary text (which reads like a dry high school Biology textbook in Japanese), but you do what you need to (A) get the project where it needs to go, and (B) maintain sanity!

How do you begin tackling something of this scope? Do you start with character dialogue or other flavor text?

AOS/ JR: Dialogue, both because it requires much more time to get right than the other text and it helps set the tone for the whole world. Also, the movie and scenario dialogue tends to be completed first in the Japanese version due to recording schedules, and similarly needs to be done first in the English for recording. We went to recording in the middle of the project, then came back to finish the rest of the text.

How did you split the work up between you? Did one of you write the main characters' spoken dialogue? If not, how did you decide which characters each of you would write?

AOS/ JR: We split the scenes up evenly, each taking every other scene, then swapping and rewriting each others' material over a few passes to ensure consistency of tone. As we went, some characters would emerge that spoke more to one of us than the other, so we might designate a scene with heavy dialogue from that character to one person. There was no splitting up by character within a scene, however, given the back-and-forth nature of dialogue. On sections with brutally demanding ADR (writing English to match Japanese lip flaps) we might sit down together and watch the video over and over, brainstorming ideas. Then one of us would go off and take a stab at it, before getting the other to check. In the non-voiced sections, we split the text up by location. Everything we did was then checked by the editor, Morgan Rushton.

Knowing that a translation is almost never exactly the same from one language to the other, any instances of major differences between what was originally in Japanese and what came through in English?

AOS/ JR: A lot changed. Some things were due to the demands of matching Japanese lip flaps, others were more "localization" issues. For example, while all the characters in the Japanese version speak (and are written) with unaccented, standard Japanese, it doesn't make sense in the context of a global story to use the same accent of English everywhere. We often compare it to classic episodes of the British SF show Dr. Who, where even aliens spoke with British accents. Modern SF and Fantasy requires a higher degree of ‘reality,' even if it's something as simple as the Star Wars formula of imperials speaking British English, and rebels speaking American, which we shamelessly borrowed.

It also led to interesting side-cases, like that of Bhujerba, a foreign land that had been colonized by the Empire some years past. We went with a Sri Lankan accent as the basis for Bhujerban speech, and flavored the written language with borrowings from Sanskrit in the way that Indian speakers of English retain words from Hindi. Similarly, the viera were given Icelandic accents to give their speech an unusual, alien quality.

Another kind of localization was a little more subtle. Where Japanese games are often very comfortable breaking immersion to deliver in-game information, Western gamers tend to prefer more wholesale immersion. So in one place in Rabanastre where the player, as Vaan, encounters a chocobo vendor, the Japanese had the vendor explain to the player that the big yellow birds he saw behind him were chocobos, and that they could be ridden. If we're in character as Vaan, of course, this is very immersion-breaking, as a street-wise orphan would certainly know what a chocobo was. So, the English version has the vendor lamenting that some guy rode off on one of his chocobos the other day without paying. It's the same information as the Japanese provides (the birds are called chocobos, you can ride them, and you have to pay for the privilege), but couched very differently.

Other things include the previously mentioned Victorian-styled bestiary, and using metered verse with an unusual rhyme scheme for the speech of the godlike Occurians. This latter move came about as a solution to the problem presented by the voice processing used for the Occurians in the Japanese. The multiple layers of voice in the Japanese had neat, otherworldly sound, but made it very hard to make out what was being said. This was helped by the on-by-default movie subtitles in the Japanese version. However, the US version had movie subtitles off by default, so we needed something else to differentiate their speech. The actress we used for the Occurian Gerun, Bernice Stegers, is a British stage actress, and she knew exactly what to do with the lines.

Who had the idea to write the dialogue in the sort of faux-Victorian dialect? I assume you did it to keep this in line with the other Ivalice-set games that you've also worked on?

AOS/ JR: It was mix of dialects, really. British for the imperials, mid 20th-century American English for the Rabanastre rebels, with a spread on both sides from colloquial speech, like Bagam'non and his crew, to the more arch "Victorian" dialect of the Judges. We cared more about making it true to the world of FFXII than true to any greater idea of what Ivalice should be.

Speaking of the other games, knowing that FFXII was sort of part of a larger tapestry, did you try to have specific callbacks to those games that didn't originally come through in the Japanese script?

AOS/ JR: Nothing serious, but there was a bit of an Ivalice easter egg in a scene with Vaan, Penelo, and Larsa joking around in the background where we had them use some dialogue from the original FFT English translation. "I got a good feeling. This is the way!" among other things. On the subject of nostalgia Easter eggs, there's also Gibbs and Deweg who were unnamed soldiers in the Japanese version, though this is obviously more an FF throwback than anything Ivalice. And as a continuation of a "tradition" Alex started on FFX, every FF game he's worked on has snuck in a reference to a certain spoony bard, and FFXII is no exception.

How much latitude did you actually have with changing things? Where there any disagreements between you and the Square Enix staff?

AOS/ JR: We had considerable leeway, especially with casting issues. Though we occasionally raised a few eyebrows, (for example, with the casting of Fran) and there were budget questions with the use of a young actor for such a main character as Larsa, which tends to be more costly than using an adult woman to voice the young boy parts. Mostly, the raised eyebrows were more curiosity than disagreement, and a little explanation was all that was required to get the team on our side. There was probably only one contentious moment, revolving around our decision to have the actor who played Gabranth (Michael E. Rodgers) mimic his character's twin brother Basch's voice (voiced by Keith Ferguson) in the scene where Gabranth is impersonating his twin. In the Japanese version, the two actor's voices play over one another in a sort of dream-sequence, but we opted to go for the arguably more "realistic" sound. The debate over which way to go came after the recording was finished, and eventually the team sided with us, but there were definitely those on the team that chafed at what was essentially a directorial decision being made by the translation team (albeit with the blessing of the voice director).

AOS: The raised dev-team eyebrows on Nicole Fantl were purely because the voice was so different from the Japanese, in a more markedly obvious way than our stylizations on the other accents affected the voices of characters like Ondore and Basch. It only took an explanation of our reasonings to sell the new take on the viera, though. Thumbs up to the FFXII dev team for being so open-minded. It's rare.

As for increased costs of hiring actual children, yes, those are the reasons: additional studio time for getting through something like acting to lip flaps with a child actor who doesn't have a lot of experience with that (it takes forever with adult actors who aren't used to ADR recording too), and there are extra costs tacked on by SAG for things like tutors. All well worth it, in our view, especially when you get a great performance like Johnny McKeown's for Larsa.

A total side-benefit to having Johnny come in was that his mother, the talented Tracy Ullman, also came to the studio so we got to meet her, which was fun.

Any favorite characters to write?

AOS/ JR: Ondore, his interstitial pieces particularly. Also Fran and the other viera with their unique accent. The Occuria were challenging and fun as mentioned above. Just from the strength of their characters, we loved the classic Matsuno characters, like Balthier, who are always a joy to write for. This includes the judges without exception, even the incredibly tricky scene with Drace confronting Vayne.

Honorable mention goes to Al-Cid, who had extremely long-winded lines delivered straight to camera, making writing to the lip flaps a considerable challenge. I know we had to adjust a few of them on the fly to match the voice actor's colorful performance. Luckily, David Rasner was both a good sport, and a master of ADR synching. He and Migelo (voiced by the inimitable John DiMaggio) were two characters that became much more fun with the spin the voice actors gave them.